Dissenting Voices

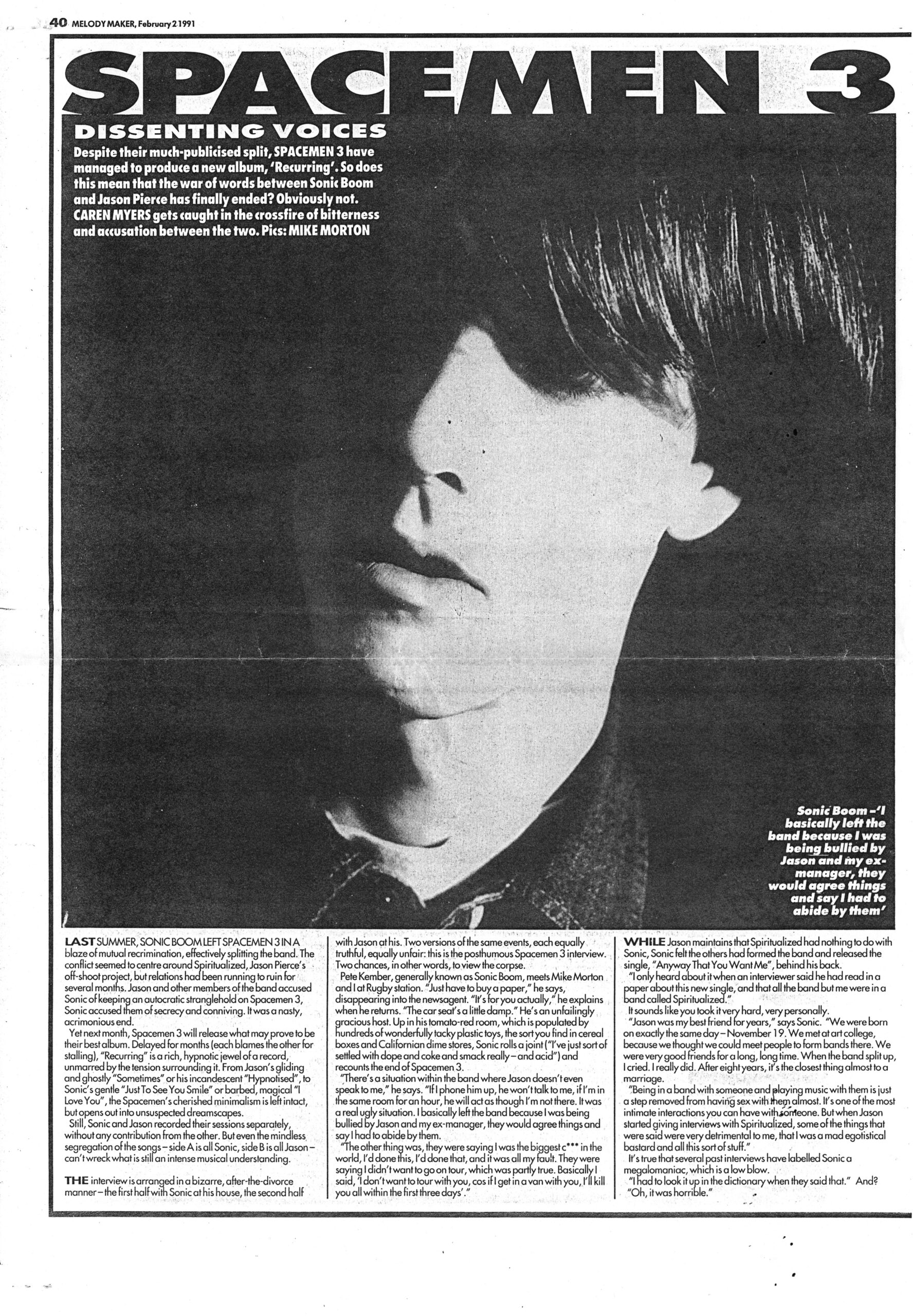

Despite their much-publicised split, Spacemen 3 have managed to produce a new album, ‘Recurring’. So does this mean that the war of words between Sonic Boom and Jason Pierce has finally ended? Obviously not. Caren Myers gets caught in the crossfire of bitterness and accusation between the two. Pics: Mike Morton.

Last summer, Sonic Boom left Spacemen 3 in a blaze of mutual recrimination, effectively splitting the band. The conflict seemed to centre around Spiritualized, Jason Pierce’s off-shoot project, but relations had been running to ruin for several months. Jason and other members of the band accused Sonic of keeping an autocratic stranglehold on Spacemen 3, Sonic accused them of secrecy and conniving. It was a nasty, acrimonious end.

Yet next month, Spacemen 3 will release what may prove to be their best album. Delayed for months (each blames the other for stalling), “Recurring” is a rich, hypnotic jewel of a record, unmarred by the tension surrounding it. From Jason’s gliding and ghostly “Sometimes” or his incandescent “Hypnotised”, to Sonic’s gentle “Just To See You Smile” or barbed, magical “I Love You”, the Spacemen’s cherished minimalism is left intact, but opens out into unsuspected dreamscapes.

Still, Sonic and Jason recorded their sessions separately, without any contribution from the other. But even the mindless segregation of the songs – side A is all Sonic, side B is all Jason – can’t wreck what is still an intense musical understanding.

The interview is arranged in a bizarre, after-the-divorce manner – the first half with Sonic at his house, the second half with Jason at his. Two versions of the same events, each equally truthful, equally unfair: this is the posthumous Spacemen 3 interview. Two chances, in other words, to view the corpse.

Pete Kember, generally known as Sonic Boom, meets Mike Morton and I at Rugby station. “Just have to buy a paper,” he says, disappearing into the newsagent. “It’s for you actually,” he explains when he returns. “The car seat is a little damp.” He’s an unfailingly gracious host. Up in his tomato-red room, which is populated by hundreds of wonderfully tacky plastic toys, the sort you find in cereal boxes and Californian dime stores, Sonic rolls a joint (“I’ve just sort of settled with dope and coke and smack really – and acid”) and recounts the end of Spacemen 3.

“There’s a situation within the band where Jason doesn’t even speak to me,” he says. “If I phone him up, he won’t talk to me, if I’m in the same room for an hour, he will act as though I’m not there. It was a real ugly situation. I basically left the band because I was being bullied by Jason and my ex-manager, they would agree things and say I had to abide by them.

“The other thing was they were saying I was the biggest c*** in the world, I’d done this, I’d done that, and it was all my fault. They were saying I didn’t want to go on tour, which was partly true. Basically I said, ‘I don’t want to tour with you, cos if I get in a van with you, I’ll kill you all within the first three days’.”

While Jason maintains that Spiritualized had nothing to do with Sonic, Sonic felt that the others had formed the band and released the single, “Anyway That You Want Me”, behind his back.

“I only heard about it when an interviewer said he had read in a paper about this new single, and that all the band but me were in a band called Spiritualized.”

It sounds like you took it very hard, very personally.

“Jason was my best friend for years,” says Sonic. “We were born on exactly the same day – November 19. We met at art college, because we thought we could meet people to form bands there. We were very good friends for a long, long time. When the band split up, I cried. I really did. After eight years, it’s the closest thing to a marriage.

“Being in a band with someone and playing music with them is just a step removed from having sex with them almost. It’s one of the most intimate interactions you can have with someone. But when Jason started giving interviews with Spiritualized, some of the things that were said were very detrimental to me, that I was a mad egotistical bastard and all this sort of stuff.”

It’s true that several past interviews have labelled Sonic a megalomaniac, which is a low blow.

“I had to look it up in the dictionary when they said that.” And? “Oh it was horrible.”

Sonic pauses for a toke. “Another thing that caused a lot of problems is that my passion for drugs hasn’t decreased over the last 10 years,” he says, with surprising candour. “And there was perhaps a bit of a conflict with people in Spiritualized being alkies when I was taking drugs. I didn’t particularly feel that was a problem, except I didn’t allow them to be pissed for playing. The drugs I take I can play on, but you can’t do that with alcohol unfortunately, it’s a bit like driving.

“I’m sure there was some resentment about that. The band had always been projected as being a drug band, and they’d all gone along with it. There seemed to be some resentment that we were getting attention for this – not from the police – but perhaps their parents didn’t like it.”

Your parents must be pretty tolerant though.

“Yeah, they’re pretty good. They know obviously that I’ve been addicted to things, they’ve got a pretty good idea what I get up to, they know that I get methadone at the moment.” Mike Morton looks suddenly interested. Sonic jumps up to show us the bottle, but it’s temporarily misplaced.

“It’s a green liquid, it’s lot lots of sugar and syrup in it,” he describes. “It’s free, it’s a stronger drug than heroin and they give it out free! So I go and pick it up twice a week. Equally you can get dexedrin…”

“But how can you just get that?” interrupts Morton.

“What you have to do is, there’s a place in Rugby and you go in and you talk to Wayne, or Barry, and you say ‘I’ve got a bit of a habit, Barry, I’m doing a gram and a half of heroin a day’, or ‘I’ve been doing both. I’m getting a bit pissed off having to shell out the money for it, what can you do for me?’ And the most you have to do is give them a urine sample. But everyone’s happy, no-one’s overdosing, everyone’s getting clean drugs, no-one’s got hygiene problems and they get clean syringes.”

To prove his point, he rummages around in the closet and produces a carboard box, one of the care packages they give out. “You get 10 syringes,” he says, holding each item up to its best advantage. I feel like I’m in a game show. “A packet of condoms, they give you a tube to put all your syringes in, it’s all free, and you get 10 wipes, a packet of matches, sometimes injectable ampoules.”

The single “Big City” is a dream of nightlife utopia, where Sonic’s fey whisper “Bright lights, big city, cool, cool people” is driven along by a hard Suicide-style beat.

“I’ve tried to sum up in that song the feeling of going to Happy Mondays gigs, where everybody’s dancing and enjoying themselves, there’s no fighting, people are tripping. For my part, I wanted this album to be very up, a sort of party album. I wanted it to be how I was feeling at the time, which was, ironically, really enjoying myself.”

In the course of the conversation, Sonic talks about the Victorians who experimented eating two pounds of hash (“Apparently it would put them to sleep for a few weeks”), his dreams (“They’re often about drugs, you get ‘em and you’re just about to take them and you wake up”), kids, hair transplants and being a bully when he was six years old.

He also talks about life after the Spacemen.

“I’m getting a new band together, I’m recording a new album. The songs aren’t going to change, it’ll still be me. I would have continued as Spacemen 3, but they basically wangled it so that I don’t have the rights to the name any more. And Jason has refused to have meetings to get things sorted out.”

Perhaps he’s just shy and can’t face you.

“He may be shy when it suits him, but he’s not shy. He’s a conniving, sneaky little f***ing sewer rat, I know that, I’ve told him not to bother. I don’t want to know, I’ trying to get on with my life. Cos I just wanted to get it all sorted out and move on, and it was all getting dragged on and on and on. I’ve tried to communicate with him and…” he doesn’t bother to finish.

Something about that reminds me of the last song on his side, a poisonous tribute to a love gone wrong, seething with self-reproach. It goes something like “You took my heart and you tore it to pieces/You gave me love and then quickly retrieved it/Why couldn’t I see”. The boy-girl connotations aside, “Why Couldn’t I See” is about Jason, isn’t it?

“Who said that?” demands Sonic, getting up and walking out. “It is actually,” he says, stepping back in. “But I’ve never said it.”

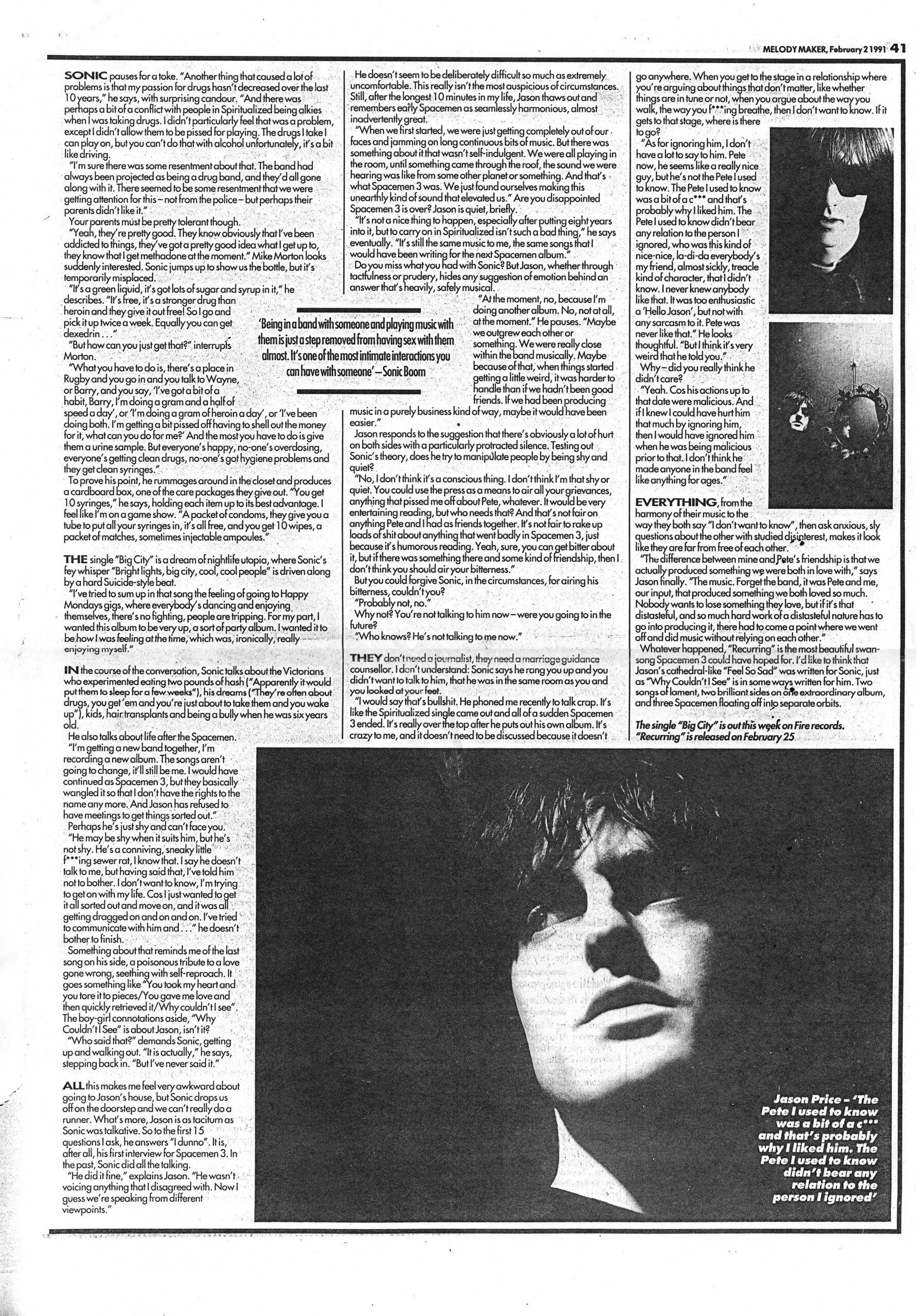

All this makes me feel very awkward about going to Jason’s house, but Sonic drop sus off on the doorstep and we can’t really do a runner. What’s more, Jason is as taciturn as Sonic was talkative. So to the first 15 questions I ask, he answers “I dunno”. It is, after all, his first interview for Spacemen 3. In the past, Sonic did all the talking/

“He did it fine,” explains Jason. “He wasn’t voicing anything that I disagreed with. Now I guess we’re speaking from different viewpoints.”

He doesn’t seem to be deliberately difficult so much as extremely uncomfortable. The reality isn’t the most auspicious of circumstances. Still, after the longest 10 minutes in my life, Jason thaws out and remembers early Spacemen as seamlessly harmonious, almost inadvertently great.

“When we first started, we were just getting completely out of our faces and jamming on long continuous bits of music. But there was something about it that wasn’t self-indulgent. We were all playing in the room, until something came through the roof, the sound we were hearing was like from some other planet or something. And that’s what Spacemen 3 was. We just found ourselves making this unearthly kind of sound that elevated us.” Are you disappointed Spacemen 3 is over? Jason is quiet, briefly.

“It’s not a nice thing to happen, especially after putting eight years into it, but to carry on in Spiritualized isn’t such a bad thing,” he says eventually. “It’s still the same music to me, the same songs that I would have been writing for the next Spacemen album.”

Do you miss what you had with Sonic? But Jason, whether through tactfulness or prudery, hides any suggestion of emotion behind an answer that’s heavily, safely musical.

“At the moment, no, because I’m doing another album. No, not at all, at the moment.” He pauses. “Maybe we outgrew each other or something. We were really close within the band musically. Maybe because of that, when things started getting a little weird, it was harder to handle than if we hadn’t been good friends. If we had been producing music in a purely business kind of way, maybe it would have been easier.”

Jason responds to the suggestion that there’s obviously a lot of hurt on both sides with a particularly protracted silence. Testing out Sonic’s theory, does he try to manipulate people by being shy and quiet?

“No, I don’t think it’s a conscious thing. I don’t think I’m that shy or quiet. You could use the press as a means to air all your grievances, anything that pissed me off about Pete, whatever. It would be very entertaining reading, but who needs that? And that’s not fair on anything Pete and I had as friends together. It’s not fair to rake up loads of shit about anything that went badly in Spacemen 3, just because it’s humorous reading. Yeah, sure, you can get bitter about it, but if there was something there and some kind of friendship, then I don’t think you should air your bitterness.”

But you could forgive Sonic, in the circumstances, for airing his bitterness, couldn’t you?

“Probably not, no.”

Why not? You’re not talking to him now – were you going to in the future?

“Who knows? He’s not talking to me now.”

They don’t need a journalist, they need a marriage guidance counsellor. I don’t understand: Sonic says he rang you up and you didn’t want to talk to him, that he was in the same room as you and you looked at your feet.

“I would say that’s bullshit. He phoned me recently to talk crap. It’s like the Spiritualized single came out and all of a sudden Spacemen 3 ended. It’s really over the top after he puts out his own album. It’s crazy to me, and it doesn’t need to be discussed because it doesn’t go anywhere. When you get to the stage in a relationship where you’re arguing about things that don’t matter, like whether things are in tune or not, when you argue about the way you walk, the way you f***ing breathe, then I don’t want to know. If it gets to that stage, where is there to go?

“As for ignoring him, I don’t have a lot to say to him. Pete now, he seems like a really nice guy, but he’s not the Pete I used to know. The Pete I used to know was a bit of a c*** and that’s probably why I liked him. The Pete I used to know didn’t bear any relation to the person I ignored, who was this kind of nice-nice, la-di-da everybody’s my friend, almost sickly, treacle kind of character, that I didn’t know. I never knew anybody like that. It was too enthusiastic a ‘Hello Jason’, but not with any sarcasm to it. Pete was never like that.” He looks thoughtful. “But I think it’s very weird that he told you.”

Why – did you really think he didn’t care?

“Yeah. Cos his actions up to that date were malicious. And if I knew I could have hurt him that much by ignoring him, then I would have ignored him when he was being malicious prior to that. I don’t think he made anyone in the band feel like anything for ages.”

Everything, from the harmony of their music to the way they both say “I don’t want to know”, then ask anxiously, sly questions about the other with studied disinterest, makes it look like they are far from free of each other.

“The difference between mine and Pete’s friendship is that we actually produced something we were both in love with,” says Jason finally. “The music. Forget the band, it was Pete and me, our input, that produced something we both loved so much. Nobody wants to lose something they love, but if it’s that distasteful, and so much hard work of a distasteful nature has to go into producing it, there had to come a point were we went off and did music without relying on each other.”

Whatever happened, “Recurring” is the most beautiful swan-song Spacemen 3 could have hoped for. I’d like to think that Jason’s cathedral-like “Feel So Sad” was written for Sonic, just as “Why Couldn’t I See” is in some ways written for him. Two songs of lament, two brilliant sides on one extraordinary album, and three Spacemen floating off into separate orbits.

The single “Big City” is out this week in Fire records. “Recurring” is released on February 25.