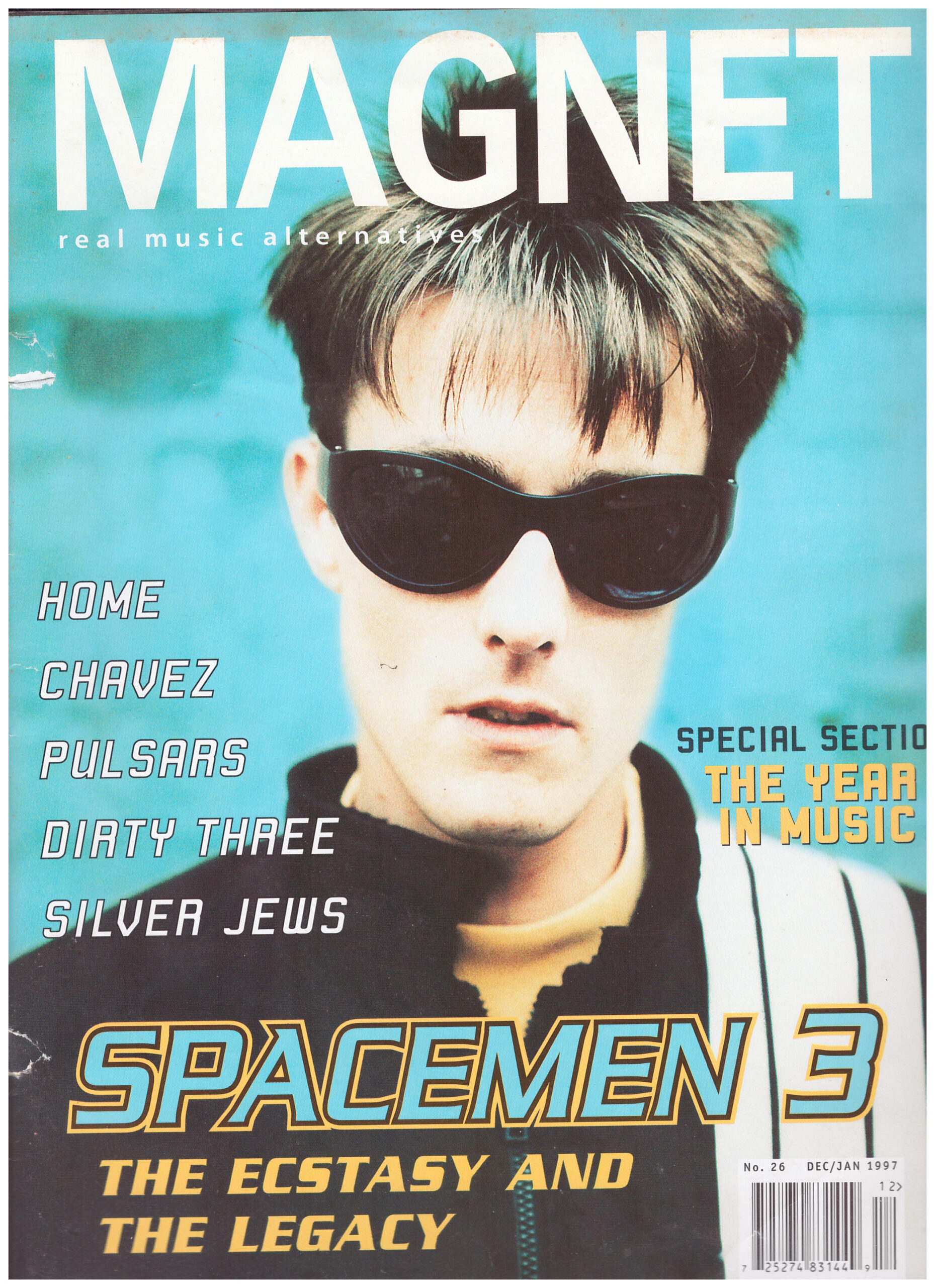

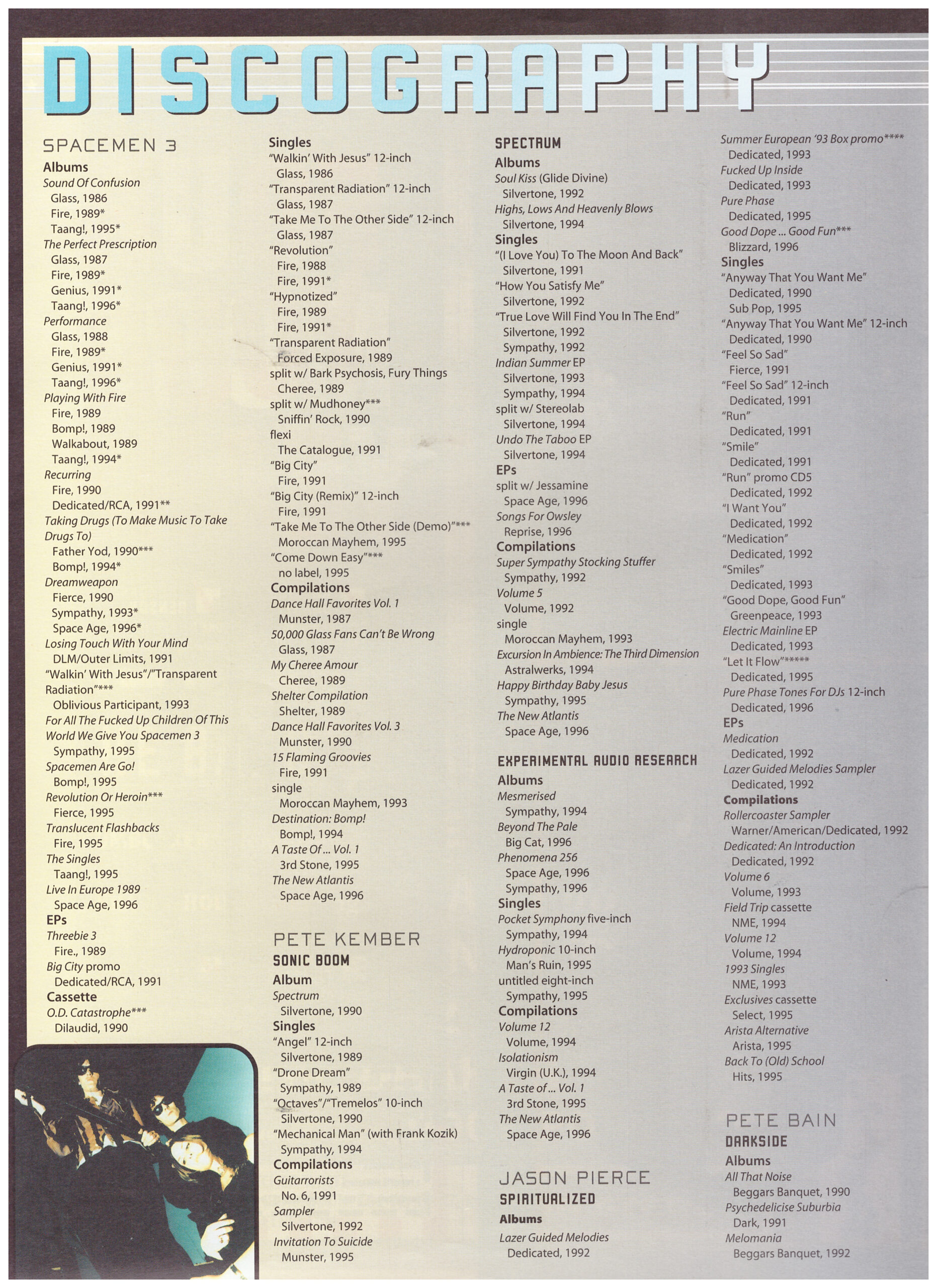

Spacemen 3

Things Will Never Be The Same

By Fred Mills

Photos by Christian Lantry

“Freefalling through time, turning galaxies into chocolate bars, forging a different course through the badly fried brains of the -80s.” – NME, 1988

“They can do it all – turn you on, threaten you, make it all seem worth-while, Spacemen 3 opt for colour, space and sensuality, and come up with the last word in English psychedelia.” – Melody Maker, 1989

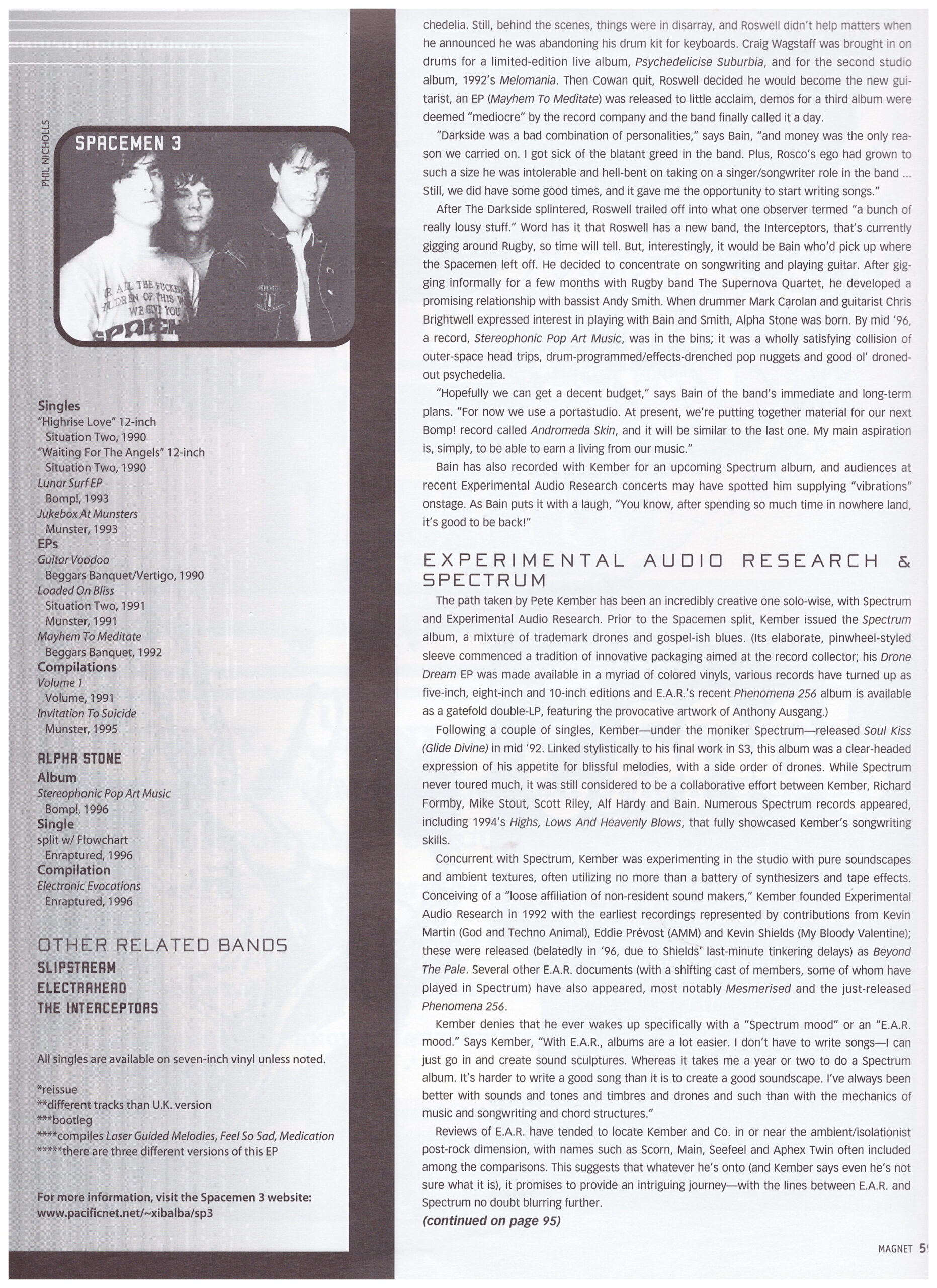

During a brief five-album, seven-year existence, dimensional warriors Spacemen 3 lived fast, played hard and eventually left behind an attractive enough corpse to inspire rock ‘n’ roll collectors, writers and musicians alike. The latter group of S3 acolytes in particular have built upon the band’s sound, often mutating and transmogrifying S3’s aural hedonism successfully enough to qualify as new-era pioneers themselves – names like Jessamine, Bardo Pond, Labradford, Magnog, Brian Jonestown Massacre, Windy & Carl, Füxa, et al. Too, the Spacemen spawned a handful of subsequent ensembles that have elaborated and refined the S3 vision to arrive, at the tail end of 1996, intact and aiming to blow minds even further. Herein, find this legendary band’s tale, and more.

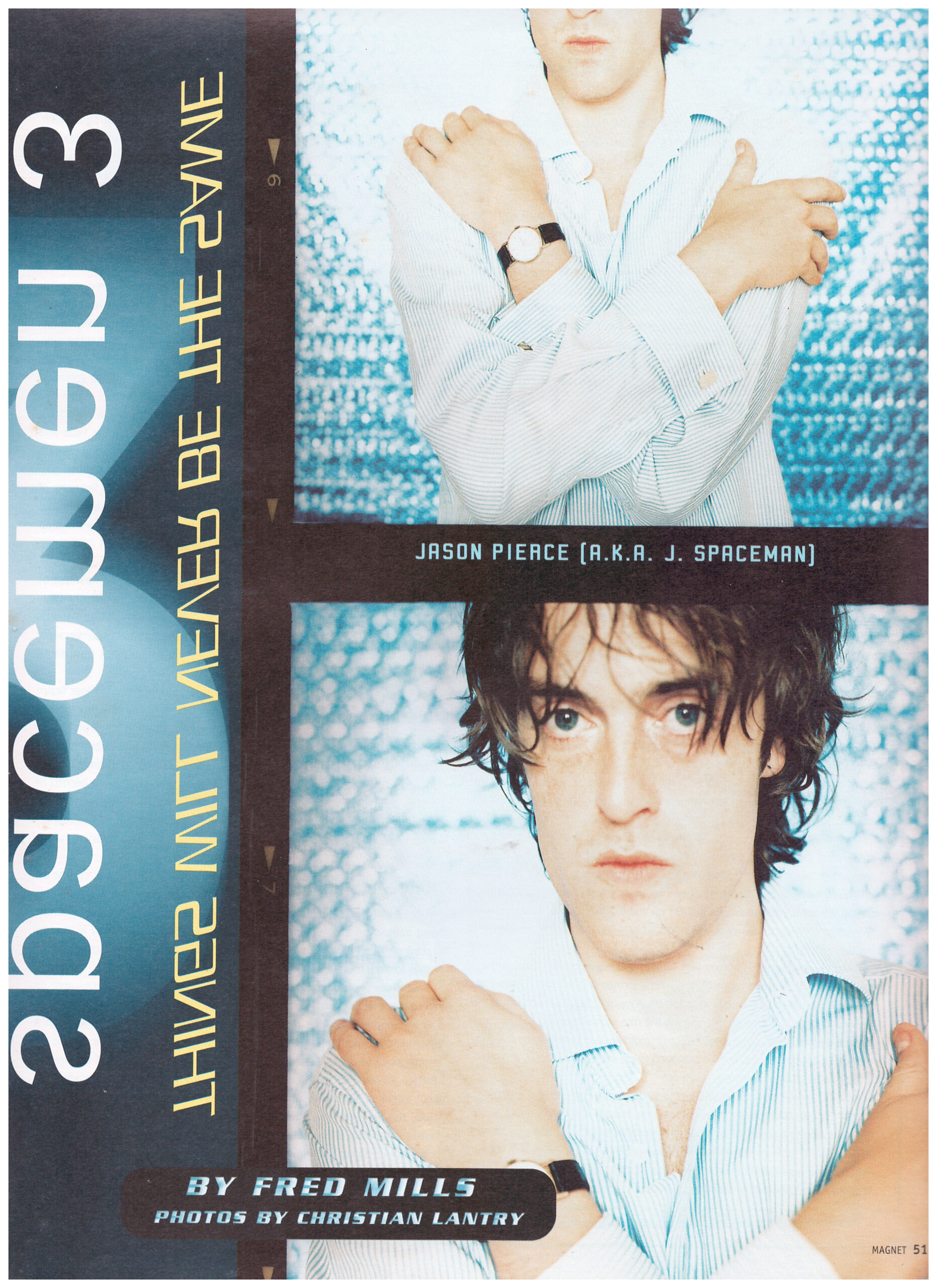

The small, unassuming, middle class burg of Rugby, England, is situated in the dead centre of the country and is considered a commerce hub and not much more. For Rugby teens, then, the options proposed by rock ‘n’ roll would frequently appear more attractive than a career loading and unloading trucks. “Just a tiny town, same story – any entertainment, you had to make it yourself,” recalls Jason Pierce, who figures significantly in our story. “I got a guitar at age seven – just an acoustic, no lessons. That kept me busy… When I was 14, I bought The Stooges’ Raw Power and I listened to nothing but that for a year… Rugby’s basically just a distribution centre, so I guess drugs came through the town a bit, too!”

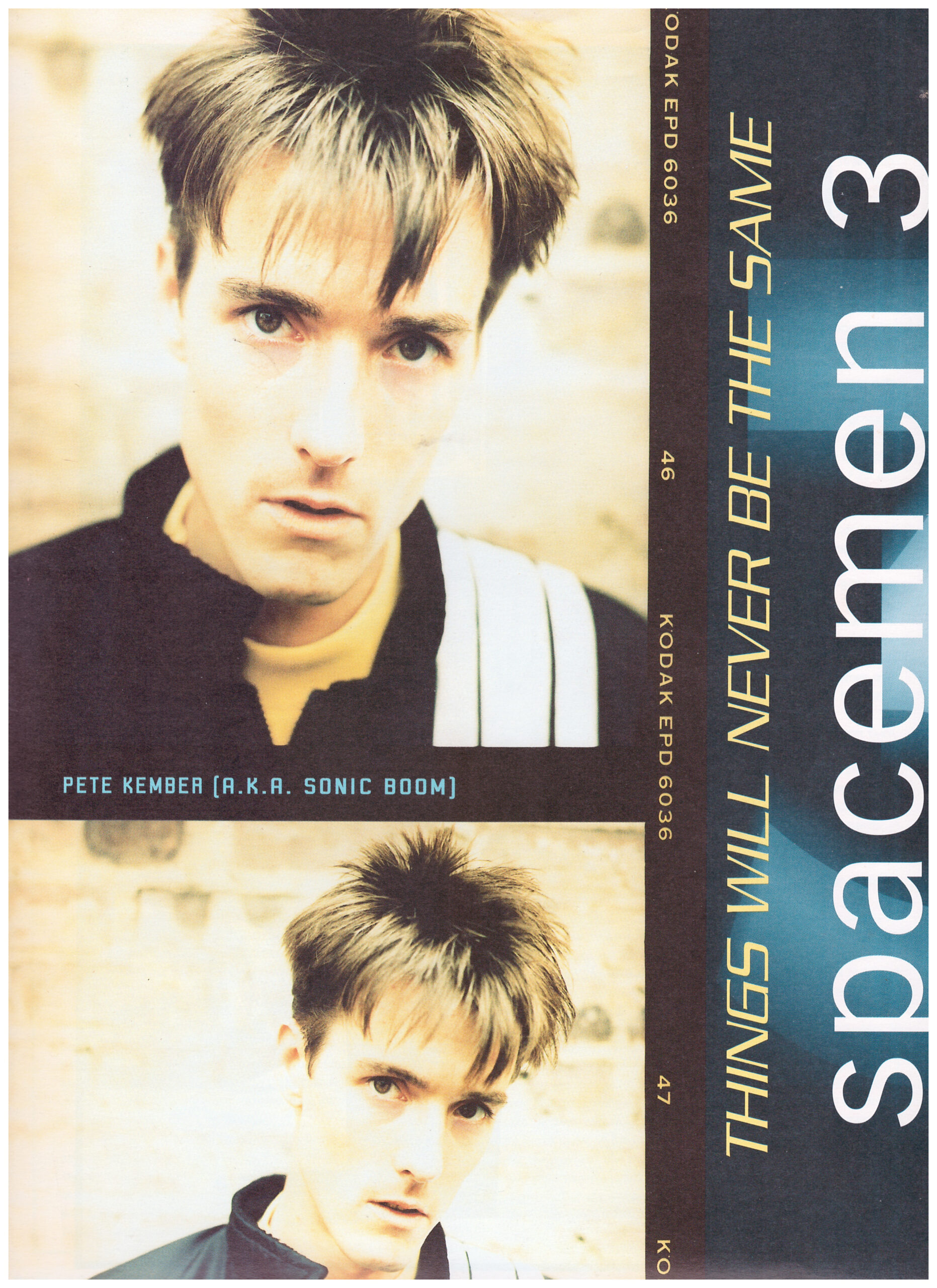

Adds Pete Kember, another of our central characters, “Particularly in my teenage years, a lot of the stuff in music that I related to was very important, helping you get through the problems with growing up. I started collecting records when I was about 11 or 12. The first record I bought, I think, was ‘Denis’ by blondie, or maybe ‘Jocko Homo’ by Devo. And I got a copy of the first Velvets album in 1980 because I was interested in modern art and read about them in an Andy Warhol book… I had gotten a guitar at the age of 13, and knew before I turned 14 that I was gonna play music.”

Soon enough, teenage consciousness would get its necessary raising, via safety pins, suggests our third player, Pete Bain: “Watching Top Of The Pops and seeing The Sweet, Bowie… Listening to The John Peel Show under the covers, on an old valve radio… Peel was describing in his usual droll voice about being pelted with mud and beer cans whilst comparing an outdoor rock festival – ‘Well, everyone’s got their problems,’ he said, and then he played ‘Problems’ by the Sex Pistols.”

It didn’t take our three heroes very long to find one another. Bain was hanging around with a friend named Stick, who’d formed a band with Pierce called Indian Scalp, which Bain recalls as being Bauhaus-like, “tight and dynamic. Pete Kember hung around the band and took the role of manager for a while. At the same time, I was in a band called Noise On Independent Street. I was the drummer and a pretty bad one, but we managed to get some songs together. It was a loose affair and didn’t last long.”

Nor did Indian Scalp. But while attending Rugby Art College, Pierce and Kember began collaborating musically. Pierce, though self-trained, was exhibiting traits akin to a prodigy’s; Kember once described his bandmate as being able to “practically pick up any stringed instrument and play it.” Whereas Kember was more of a wilful primitive enamoured with the possibilities of sound: “Bryan Gregory from the Cramps, those big sheets of feedback and fuzz, very minimal stuff. And John Cale to a certain extent, what he used to do with a viola – that sort of monotone-drone. The Rolling Stones’ ‘Satisfaction,’ that minimalism and pure Troggery of that riff!”

Spacemen 3 had its beginnings around the tail end of 1982 in the spacious attic bedroom of Tim Morris, who’d been in Noise On Independent Street with Bain. Bain (now on bass) recalls that “the practices sounded great – when we were in tune!” Apparently confidence was in no short supply, either; the young musicians adopted the habit of announcing to anyone who approached them, “We’re spacemen,” which in turn provided them with both an image and a name. (In an early Forced Exposure interview, Kember said that they’d had a poster for “The Spacemen,” but as he hated the ‘50s pop band connotations, a new poster was designed to read, “Are you dreams at night 3 sizes too big?” The “3” stuck.)

“It wasn’t long before we played gigs,” says Bain, “the first at a very raucous house party that ended being broken up by police. The next two were at The Exchange, a grubby bikers pub. We played songs like ‘Some Kind Of Love,’ ‘2:35,’ ‘TV Eye,’ ‘Funhouse.’ The first gig wasn’t too hot. Jason was shaking with nerves; Tim and myself hadn’t ingested the same substances as the other two, and half the audience walked out. Jason said to me afterwards, ‘We’re gonna be big – the audience walked out of Alice Cooper’s first gig, too!’”

The first incarnation of Spacemen 3 didn’t last long, as Pierce left town for a different college. Bain and Morris formed a garage band called The Push and achieved some local popularity. Then Pierce returned to Rugby, hooking back up with Kember in early ’84. The pair recruited Nicholas “Natty” Brooker to play drums; a demo session yielded embryonic but powerful versions of songs that would wind up on Spacemen 3’s first two albums. The collision of bluesy melodicism and fuzztone overdrive was an alien, exciting sound emerging out of the dull British pop scene.

Bain soon returned to the fold and a new set of demos was recorded by the four-piece in January 1986, in nearby Northampton. Soon enough, Glass Records offered a two-album contract, and the Spacemen went into a Birmingham studio and knocked out their debut LP, Sound Of Confusion, in five days.

This record (bearing the personnel credits “Peter Gunn, Jason, Bassman, N. Brooker”) and its follow-up a few months later, the Walkin’ With Jesus EP (Kember switching from “Peter Gunn” to “Sonic Boom” in the interim), defined the larger-than-life, fuzz/feedback/distortion, extended drone S3 sound, with epic translations of the 13th Floor Elevators’ “Rollercoaster,” The Stooges’ “Little Doll” and a handful of equally brain-melting originals. Some of these originals were rewrites of/homages to existing material, like the one-chord thud of “O.D. Catastrophe,” which used the Stooges’ “TV Eye” as jumping-off point, and “Mary-Anne,” a remake/remodel of The Misunderstood’s “Just One Time.”

Reviewers duly genuflected, as did shocked concert audiences caught off guard by the band’s volume, the retro-psychedelic light show and what was perceived as a non-pop star stance; entire sets were frequently performed with the band seated on stools. (Later, Kember would demystify things in Forces Exposure: “I can hardly play guitar and don’t understand a lot of chords and I always found it much easier to sit down and play.”)

Antiheroes or not, the Spacemen grew quickly beyond cult status – and, on their second album, outgrew their heavy psych style that other groups like Loop and My Bloody Valentine had begun to emulate. In early ’87, Spacemen 3 assembled at Rugby’s VHF Studio to record what would be their classic LP. Shortly prior to rehearsals, drummer Brooker had been replaced by Stewart “Rosco” Roswell, and as luck would have it, VHF was about to upgrade from eight tracks to 16, so the four musicians agreed to help with the conversion under the provision that they could have unlimited time there. S3 basically moved in for several months, smoked many ounces of dope and recorded version upon version of their new songs to distil them down into…

The Perfect Prescription: a concept album devoted to chronicling the inception, take-off, peak and plateau and, ultimately, the crash of a drug experience. An unqualified masterpiece of shimmering, beatific melodies, rhythmic/dynamic tension and stylistic contrasts, the record remains a favourite among all the members of the band. Pierce in particular remembers it as being “the first I wasn’t writing songs that were based on anybody else’s songs. So ‘Walkin’ With Jesus’ was purely about what I was doing – I was kind of shocked to see the lyric written down, and, ‘Hey, that’s exactly what I was feeling! Yeah, I really want to do this, to write songs.’”

The LP also contained tributes to Lou Reed (“Ode To Street Hassle”) and the Red Krayola (“Transparent Radiation”), and as Kember will quickly point out, during its tenure the band became infamous for the liberal plundering of its record collection in concert, with covers of The Godz (“Turn On”), Bo Diddley (“It’s Alright”) and Suicide (“Che”). This influences-on-sleeves approach should have provided journalists with fertile fodder for inquiry, although the press tended to dwell more on Kember’s open advocacy of drug usage.

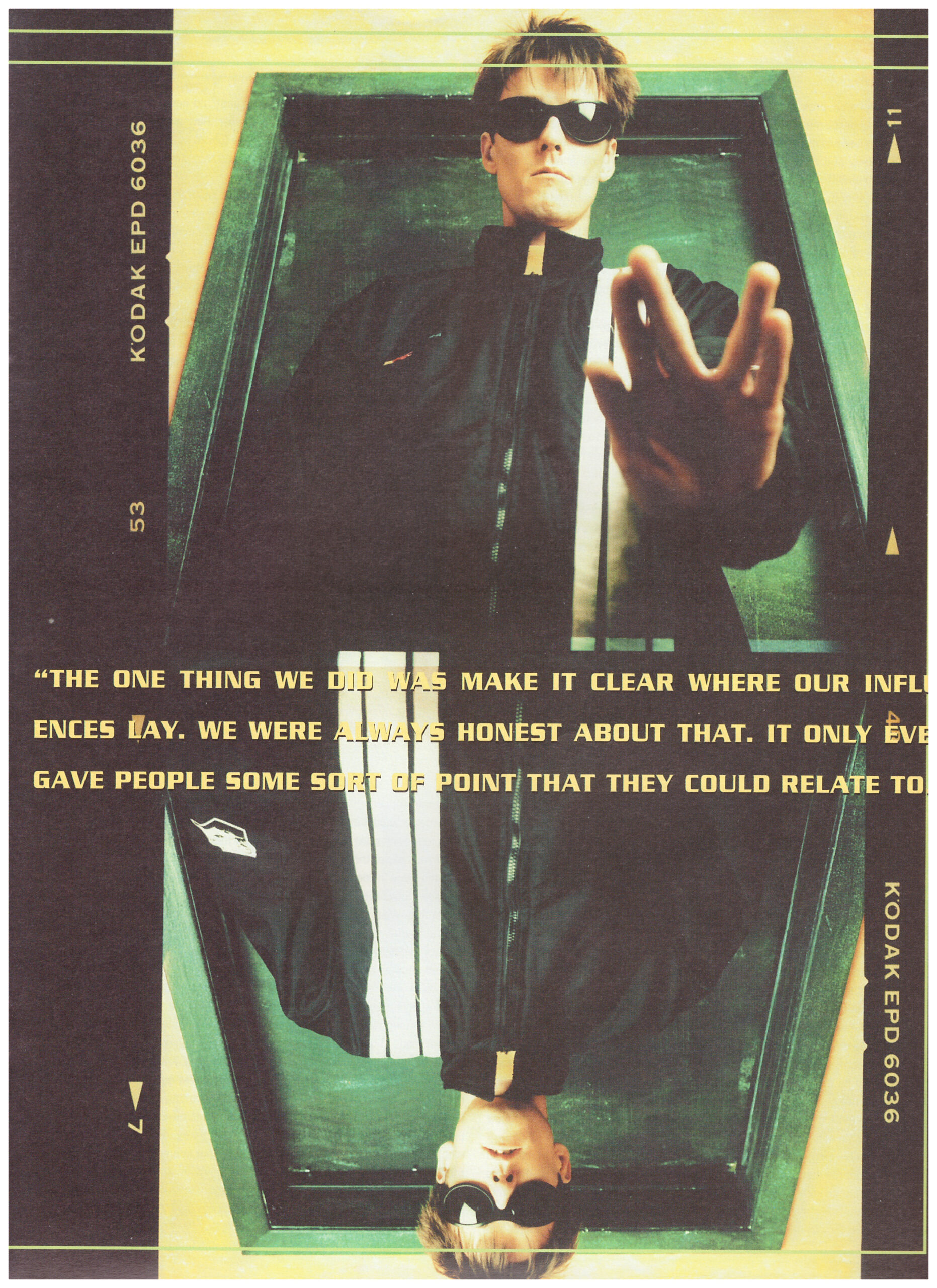

“I’ll tell you something,” reflects Kember, “the one thing we did was make it clear where our influences lay. We were always honest about that. It only ever gave people some sort of point that they could relate to, sort of go, ‘Well, maybe I should check that out because I like the stuff they’re talking about.’ I mean, I knew it was inevitable the interviewers were going to ask about the drug angle – you could tell by the looks on their faces they couldn’t believe I would say such (pro-drugs) things, thinking I couldn’t imagine this stuff would wind up in print. So I would also (do things like) list bootlegs when they’d ask me my top 10 LPs. I’d pick the records that were influential on Spacemen 3, and at least a third of them were bootlegs, like Velvet Underground things that were only known by collectors. It was important to show what was interesting to the Spacemen; for example, a song like ‘Sister Ray’ done different ways, showing different sides to a song. We did that with our songs, too – play them different ways, mix up styles. Even our cover of the Krayola’s ‘Transparent Radiation’ was after the version on Epitaph For A Legend, rather than the better-known one of Parable Of Arable Land; that was really important to us – and it almost became our own song through that! ‘Losin’ Touch With My Mind’ on Sound Of Confusion was kind of a take on the Stones’ ‘Citadel’ from Satanic Majesties. But we were always honest about it. People could then go and listen to ‘Citadel’ and go, ‘Oh, I can see that, but there’s enough difference about it, too.’ We were original enough to add to our influences, so there was no need to be ashamed about it.”

S3 moved into 1988, wowing audiences across Europe. One very stoned evening in February, at Amsterdam’s Melkweg club, was captured on tape and issued as the Performance LP. Kember would later admit it was an off night, noting that cracks were already appearing in the band. First Roswell left, aspiring to become a guitarist. Then Bain quit as well. “I desperately needed to straighten myself out, so I reluctantly left,” says Bain on his final days with the band. “Jason had asked me if I was leaving, but I couldn’t say yes or no. He said, ‘Yeah, it’s not spiritually fulfilling, is it?’ and I guess that summed it up. I don’t know – it took us a lot of work, but sometimes you lose faith in it all.”

William “Willie” Carruthers replaced Bain, and S3 then recorded its third studio album, Playing With Fire. It appeared in early ’89 and was immediately buoyed up by the U.K. chart success of the preceding single, “Revolution.” That tune’s heavy riffage, however, stylistically diverged from the rest of the album – a subdued, hypnotic affair that was destined to become the blueprint for a new generation of ambient-drone space rockers.

With press hype for S3 at a peak, all bets were on the band (which had added drummer Jon Mattock to the lineup) to take America by storm in 1989. The was not to be the case, however. Says Greg Shaw, owner of California-based Bomp! Records, “Fire Records had acquired Glass and was looking for an American licensee for Playing With Fire, was talking dollar figures to other labels and (asked Shaw) ‘Could I come up with 10 grand?’ I’d never spent that much money in my life! I borrowed it from my mother! Having the hottest record in England would create a completely new image for our label and show we could promote a new artist, because we were seen as an archive label. So we made the deal, released the record, helped organize this huge American tour – that was promptly cancelled right on the eve because Jason and Sonic had this huge fight. They put up a good front right up until the last minute.”

It’s worth pointing out that in the Reagan era, the likelihood of a revolution-talkin’/drug-takin’ band being allowed a U.S. work visa was slim. Admits Kember, “We had some drug convictions on our records. And then we had to supply our albums and press and stuff to sort of prove our case ‘worthy.’ It was very hard to find enough press that didn’t have drug references.”

By this point, too, further “problems” in the Spacemen 3 camp were accumulating. In a S3 article in The Catalogue, Fire Records’ Dave Bedford told the interviewer, “They’re a great band… They had two very strong, opposing personalities and opinions. Spacemen were more difficult than most because of having two people not really working together or speaking.”

The final Spacemen days were at hand. In 1990, Recurring was issued. It was a literal document of a band splitting apart, with one side comprised of Kember’s five tunes and the other of Pierce’s five. Personnel-wise, too, the band had become less of a self-contained unit; in addition to several friends helping out instrumentally, a third guitarist, Mark Refoy, was brought into the fold. Refoy, a longtime S3 fan, recalls he arrived “at the very teil end and only did two or three gigs with them. I went to a few of the Recurring sessions and put guitar tracks down. But things didn’t last very long.”

By the time the album appeared in the shops, the band would be gone. Kember had laid the groundwork for his escape via a solo album, Spectrum, recorded around the same time as the Recurring sessions and utilizing some of the same players (including Pierce). For his part, Pierce was already recording material for what would become his post-S3 project, Spiritualized, whose first single was a cover of the Troggs’ “Anyway That You Want Me.” This move served as the final nail in the coffin for S3; as Kember told The Catalogue, “Originally, we all knew we were going to split up after the album was recorded, pursue different projects and then reconvene in a year’s time… Then [Spiritualized] recorded ‘Anyway That You Want Me,’ which I’d suggested Spacemen 3 should cover (during the Playing With Fire sessions). There didn’t seem to me any great need for them to show they could do it… I basically said, ‘OK, if you have all these ideas, then fuck off and do it’”.

Of the same incident, Pierce says, “Spacemen hadn’t been on tour for a year and didn’t look likely to, so Spiritualized needed some product to be able to go out on tour. What the press picked up on was that I left Spacemen 3 and took the band with me. What actually happened was those guys (Carruthers, Mattock and Refoy) left individually over a period of about seven months. But is seemed crazy to let them go because they were obviously attuned to what we were doing and creating those kinds of sounds, so I kind of followed them.”

The simple truth was that Kember and Pierce had grown apart personally and ceased writing together professionally. That much is clear from statements Kember made at the time indicating he’d grown tired of sharing credit for songs he’d written “totally away from” Pierce. For his part, Pierce tends to agree, observing that the split had “mainly to do with songwriting credit. When we got to the third album, Pete started writing songs on his own, and it was the first time he’d tried to write and claim the credit. That’s why the credits on [Playing With Fire] are kind of weird. (Only “Suicide” is a joint Kember/Pierce credit.) We tried to carry on, but the next album was very weird, recorded totally separately. At the end of the day, I wasn’t prepared to have that kind of relationship with anybody in making music. And it seemed dumb to say, ‘This is my song, and that is your song.’ So, that was that.”

Well, not exactly. As is often the case with defunct but highly regarded (and sellable) bands, Spacemen 3 lives on, courtesy assorted reissues, archive projects and outright bootlegs. In fact, the discography of S3 and related bands has reached such labyrinthine proportions that it’s taken a website to unravel all the minutiae. Compiled by S3 fan Chris Barrus, “The Spacemen 3 Archives” should clear up most questions S3 fans have, and it’s appropriate to point out that a lingering source of friction between Kember and Pierce stems from the posthumous release aspect of the band’s legacy.

In 1990, not long after the breakup, a bootleg S3 album appeared entitled Dreamweapon, which hailed from a drones/tones ’88 performance. Word had it that Kember had leaked the tapes to Fierce Records, which infuriated Pierce. (Interestingly, several years later Pierce would leak a live tape, possibly in retaliation, to Fierce; it became the Revolution Or Heroin bootleg.) Around this time, Sympathy For The Record Industry’s Long Gone John struck up a relationship with Kember, who subsequently authorised Sympathy to issue S3’s ’84 Rugby demos (as For All The Fucked-Up Children Of This World) as well as an expanded version of Dreamweapon. Says Long Gone John, “When I put that out, Jason called me up and wasn’t too happy about it: ‘Man, I didn’t get paid the first time around!’ But he calmed down and asked me if I’d do a Spiritualized single. I said I’d love to – although I wasn’t surprised the next time I talked to Sonic when he said that if I did anything with Jason, that was the end of our relationship.”

Sympathy, of course, would go to the well with Kember numerous times over the years. Likewise, Bomp!’s Shaw struck his deal with Kember to release Spacemen material; Kember presented Shaw with six DATs, which have resulted thus far in two compact discs – Taking Drugs To Make Music To Take Drugs To (comprised of the 1986 Northampton demos) and Spacemen Are Go! (Recorded live in Europe in 1989). Although much of the rest of the material is live and tends towards redundancy song-wise, Shaw says there are some amazing demos waiting to be heard. “Those from The Perfect Prescription were very cool and radically different from the released versions,” says Shaw. “Sonic is an absolute perfectionist when it comes to mastering and putting together artwork, and we got as far as the artwork and even had a title, Call The Doctor,”

Enter Space Age Recordings. The label was started by Kember and Gerald Palmer, the former manager of Spacemen 3 who legally owns the masters of all the Glass/Fire-era S3 material. When Palmer got wind of Bomp!’s Call The Doctor project, things got litigious; to avoid a lawsuit and get the material released, Kember went into business with Palmer.

Pierce isn’t overjoyed with the situation. “I can go back and look at stuff I was doing then, and I guess I don’t mind it’s out there,” he says. “But is seems weird to get involved with something that is six or seven years old now. And I think Pete’s quite content to do it how he’s been doing it all along. He puts them out and he takes the money. But I haven’t seen a cent from any of it.”

Kember counters that he’d rather be involved than not: “If you’re not, it tends to come out anyway!”

Once the Prescription demos (rechristened Forged Prescriptions) are released, plus a possible similar project involving Playing With Fire demos and outtakes, Space Age plans to concentrate primarily on new projects.

Spiritualized

As indicated previously, even as Spacemen 3 was coming to an end, Jason Pierce was laying the groundwork for his new project. Certainly, Pierce’s side of Recurring had much in common stylistically with Spiritualized’s debut album.

“With the Spacemen, I was trying to chase finished products in my head,” says Pierce. “I already had the sound of the song in my head, and I was trying to get that down on tape. With the Spiritualized thing, I don’t chase any symphony; it’s a lot looser, more freeform and new. You could call us ‘minimal by design’ with the sounds we were using.”

Lazer Guided Melodies took two years to complete and finally appeared in early ’92; already, Pierce was developing a reputation as a stickler for the right mix. Meanwhile, the group – Pierce, Carruthers, Mattock, Refoy, keyboardist/guitarist Kate Radley and, on occasion, horn and string players – had honed its sound through substantial gigging. A high-profile trek across America with The Jesus And Mary Chain and Curve took place in ’92, and the band headlined Britain’s Glastonbury festival the following year. Audiences embraced the group’s miasma of blissed-out orchestral blues and gospel psychedelia.

A limited-edition live album, Fucked Up Inside, turned up in ’93, and while the second studio album was being worked on, a series of EPs kept the band’s profile high. The basic recording for Pure Phase went by fairly quickly for the core group (featuring new bassist Sean Cook). Pierce, however, fussed over the mixing until early ’95. The final product not only boasted the unusual distinction of each stereo channel having separate mixes; its tripped-out ambiance and heavy tonal rush suggested that Pierce’s intension to craft a record simultaneously “of now, but out of time as well, to be emotional and fresh after 10 years’ time” was a sound plan.

When the band toured the U.S., an American breakthrough seemed imminent. Pierce says that was never specifically the plan. “The band is not about success commercially,” he says. “The goal is to be the best we can, and to keep going forward. A lot of bands have the weird cabaret mentality of playing the hits at the same time each night. We just do it naturally… That’s the only way you can make good music, to be very selfish about it and satisfy yourself.”

(In the period following the release of Pure Phase, guitarist Refoy left Spiritualized to pursue a new project that had been brewing in his head for some months. “I got bored and needed an outlet,” says Refoy. “I kind of made my position untenable, really, because I wouldn’t work in tandem with Spiritualized.” To that end, Refoy formed Slipstream. The band’s eponymous debut LP in ’95 was an upbeat, seamless blend of psychedelic guitar mantras, slide-guitar opuses and catchy pop ditties; a new album, to be mixture of live-in-studio and Q-base computer programs, is in the works. But Refoy is quick to distance Slipstream from his previous bands, stating for the record, “Just call it a factual link more than a musical one.”)

Meanwhile, recording sessions for the third Spiritualized album commenced in late ’95 with the band making a conscious effort to jettison, according to Pierce, “all the things, such as phase tones, drones and tremolos, that people recognise as ‘our’ sound.” Two new members (drummer Damon Reece and guitarist Mike Moony) and one special guest (legendary piano player Dr. John) were recruited for the album. Due out in March, the LP is to be called Ladies And Gentlemen, We Are Floating In Space. Pierce casually describes it in terms of “’Spiritualized Rocket Shaped Songs,’ since with each of the previous albums we were trying to say what kinds of sounds we were making at that point: ‘Spiritualized Electric Mainline’ or ‘Spiritualized Lazer Guided Melodies.’”

He also offers no apologies for his meticulousness with the mixing. “That’s why we have trouble,” says Pierce. “It’s like trying to remember why something was so spontaneous and immediate. Like now, for instance – trying to remember how something happened a year ago is hard to do. But I know it’s there, and I know the mixes are there. There is the final mix that will work for the record, so I’m always chasing this sound around and using a lot of people. Just recently, I was working (on mixes) with Jim Dickinson in Memphis. Next week I’m off to L.A. for yet more mixing!

“It’s too important to just knock a record out and then just throw it out there. I’ve always said we’re trying to make music that affects people. We’re trying to make records that stand the test of time. And I’m not putting out records that we’ve already done. I use the words ‘Grandma’s recipes’ – that’s what a lot of people are satisfied with. They don’t want to push the boundaries, but just keep churning out the same things with minor changes. I wanna feel like we’re going somewhere, you know? I want to create something that’s bigger than what we’re playing. Somebody wrote about us live once, ‘It was like God playing feedback with a guitar behind the curtain.’ Well, I want it to sound like it’s several deities back there playing!”

Do doubt Spiritualized was given the opportunity to feel like much lesser deities last August and September, when the band opened a series of dates for Neil Young & Crazy Horse. (“We went down well,” says Pierce, “and I think there’s a strong link musically between him and us – just his whole attitude, the fact that he’s doing it for the music only,”)

Pierce is clearly looking toward the future these days. “I’m not into hanging on to past glories,” says Pierce. “I don’t go out and say, ‘Hey, I was in Spacemen 3!’ I’m not even satisfied with what we’re doing now – I want to do better! When I started to play music, I personally set out to be honest to myself. There’s what one guy called ‘the mathematics of music’: when people understand the mathematics of how to write a song and they have enough ability to do something similar, and there’s already a blueprint to use anyway. I think the stuff that affects me is stuff that disregards the mathematics. When you know what you’re hearing is someone singing about their own life, writing about what they do and what they’re about, but it relates to what you’re about as well – that’s the kind of stuff I go for.”

Darkside & Alpha Stone

When we last heard from Pete Bain, he had eased out of Spacemen 3 prior to the Playing With Fire sessions. After a few months in Rugby doing nothing, he ran in to a local friend, Nick Hayden, who invited him to sit in with his band. The Darkside had played on and off around Rugby since ’86, even supporting the Spacemen on occasion. Bain accepted the invitation “with no real long term commitment,” and a revitalized Darkside was soon gigging and cutting demos. The band’s trajectory, however, was to be fraught with fits, starts and problems. First, a record deal was secured and the drummer promptly quit. Rosco Roswell, Bain’s old S3 crony, turned up in time to record a single for the Situation Two label. Then, halfway into the first national tour, Hayden freaked out and didn’t show up for a gig, leaving Bain to take the role of vocalist and The Darkside to “stumble on to the end of the tour” as a trio (Bain, Roswell and guitarist Kevin Cowan).

The band did recover enough to record All That Noise for Beggars Banquet. Reviewers immediately saluted the band’s blend of classic garage and liquid psychedelia. Still, behind the scenes, things were in disarray, and Roswell didn’t help matters when he announced he was abandoning his drum kit for keyboards. Craig Wagstaff was brought in on drums for a limited-edition live album, Psychedelicise Suburbia, and for the second studio album, 1992’s Melomania. Then Cowan quit, Roswell decided he would become the new guitarist, an EP (Mayhem To Meditate) was released to little acclaim, demos for a third album were deemed “mediocre” by the record company and the band finally called it a day.

“Darkside was a bad combination of personalities,” says Bain, “and money was the only reason we carried on. I got sick of the blatant greed in the band. Plus, Rosco’s ego had grown to such a size he was intolerable and hell-bent on taking on a singer/songwriter role in the band… Still, we did have some good times, and it gave me the opportunity to start writing songs.”

After The Darkside splintered, Roswell trailed off into what one observer termed “a bunch of really lousy stuff.” Word has it that Roswell has a new band, the Interceptors, that’s currently gigging around Rugby, so time will tell. But, interestingly, it would be Bain who’d pick up where the Spacemen left off. He decided to concentrate on songwriting and playing guitar. After gigging informally for a few months with Rugby band The Supernova Quartet, he developed a promising relationship with bassist Andy Smith. When drummer Mark Carolan and guitarist Chris Brightwell expressed interest in playing with Bain and Smith, Alpha Stone was born. By mid ’96, a record, Stereophonic Pop Art Music, was in the bins; it was a wholly satisfying collision of outer-space head trips, drum-programmed/effects-drenched pop nuggets and good ol’ droned-out psychedelia.

“Hopefully we can get a decent budget,” says Bain of the band’s immediate and long-term plans. “For now we use a portastudio. At present, we’re putting together material for our next Bomp! record called Andromeda Skin, and it will be similar to the last one. My main aspiration is, simply, to be able to earn a living from our music.”

Bain has also recorded with Kember for an upcoming Spectrum album, and audiences at recent Experimental Audio Research concerts may have spotted him supplying “vibrations” onstage. As Bain puts in with a laugh, “You know, after spending so much time in nowhere land, it’s good to be back!”

Experimental Audio Research & Spectrum

The path taken by Pete Kember has been an incredibly creative one solo-wise, with Spectrum and Experimental Audio Research. Prior to the Spacemen split, Kember issued the Spectrum album, a mixture of trademark drones and gospel-ish blues. (Its elaborate, pinwheel-styled sleeve commenced a tradition of innovative packaging aimed at the record collector; his Drone Dream EP was made available in a myriad of colored vinyls, various records have turned up as five-inch, eight-inch and 10-inch editions and E.A.R.’s recent Phenomena 256 album is available as a gatefold double-LP, featuring the provocative artwork of Anthony Ausgang.)

Following a couple of singles, Kember – under the moniker Spectrum – released Soul Kiss (Glide Divine) in mid ’92. Linked stylistically to his final work in S3, this album was a clear-headed expression of his appetite for blissful melodies, with a side order of drones. While Spectrum never toured much, it was still considered to be a collaborative effort between Kember, Richard Formby, Mike Stout, Scott Riley, Alf Hardy and Bain. Numerous Spectrum records appeared, including 1994’s Highs, Lows And Heavenly Blows, that fully showcased Kember’s songwriting skills.

Concurrent with Spectrum, Kember was experimenting in the studio with pure soundscapes and ambient textures, often utilizing no more than a battery of synthesizers and tape effects. Conceiving of a “loose affiliation of non-resident sound makers,” Kember founded Experimental Audio Research in 1992 with the earliest recordings represented by contributions from Kevin Martin (God and Techno Animal), Eddie Prévost (AMM) and Kevin Shields (My Bloody Valentine); these were released (belatedly in ’96 due to Shield’s last-minute tinkering delays) as Beyond The Pale. Several other E.A.R. documents (with a shifting cast of members, some of whom have played in Spectrum) have also appeared, most notably Mesmerised and the just-released Phenomena 256.

Kember denies that he ever wakes up specifically with at “Spectrum mood” or an “E.A.R. mood.” Says Kember, “With E.A.R., albums are a lot easier. I don’t have to write songs – I can just go in and create sound sculptures. Whereas it takes me a year or two to do a Spectrum album. It’s harder to write a good song than it is to create a good soundscape. I’ve always been better with sounds and tones and timbres and drones and such than with the mechanics of music and songwriting and chord structures.”

Reviews of E.A.R. have tended to locate Kember and Co. in or near the ambient/isolationist post-rock dimension, with names such as Scorn, Main, Seefeel and Aphex Twin often included among the comparisons. This suggests that whatever he’s onto (and Kember says even he’s not sure what it is), it promises to provide an intriguing journey – with the lines between E.A.R. and Spectrum no doubt blurring further.

Last summer, Kember toured E.A.R. across the U.S. with Bain, Tom Prentice on electric viola and Alf Hardy treating the sound. Opening the tour – and frequently joining E.A.R. onstage as well – was a who’s-who of current ambient/space/post-rock outfits: Jessamine (with whom Kember recorded the Spectrum A Pox On You EP), Magnog, Bowery Electric, Bardo Pond, Tortoise, Windy & Carl, Brian Jonestown Massacre and Music Arch Deluxe. Kember clearly thrives on such interactions, saying, “I think of them as contemporaries. E.A.R. is a collaboration, and I do thing that at certain times there seems to be more cross-pollination and experimentation than at others, when people want to do more than just write ‘tacky pop songs.’”

Reprise Records just issued Spectrum’s Songs For Owsley, an EP featuring no guitars – just vintage analog synths, theremin and vocodor; a full-length follow-up, Forever Alien, is slated for early ’97. “There has always been that experimental side,” says Kember. “Like ‘Ecstasy Symphony’ on Perfect Prescription or ‘Phase Me Out Gently’ on Soul Kiss. Through working on E.A.R. projects and focusing on the experimental side, I realized that seemed to be the way to go with Spectrum. A lot of it is inspired by the experimental music, tape manipulations and musique concrete of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, part of the BBC in the ‘50s and ‘60s, that used to create radiophonic sounds and science fiction themes, with lots of theremin and primitive electronic gear. So my new stuff is quite otherworldly.”

If that wasn’t enough, there’s more in the immediate pipeline: an E.A.R. project with isolationist/ambient artist Thomas Köner for the Drunken Fish label and an E.A.R. analog synthesizer epic for Bomp! called 3D Dose (inspired by, as Kember puts it, “the benign, lots-of-information aspects of the DMT trip.”)

“People like Sonic understand the drug element,” says Bomp!’s Shaw. “Not in a decadent manner, but in an opening of the windows of the mind and seeing from a different perspective. I think he sees that artistically, and was creatively challenged by the drug.”

“What I’m trying to do,” concludes Kember, “is achieve with more abstract sounds, to touch deeper moods and feelings through the music and sounds. What I always aimed for, what we aimed for in the Spacemen, was honesty and purity. Those were the criteria that were uppermost. Something about music is very spiritual, and it can be very fulfilling. There’s few things better than to make music that can be spiritually fulfilling to people.”

As such, it’s reasonable to conclude that, despite a personal and professional divergence some seven-odd years ago, Pete Kember and Jason Pierce have remained philosophically very close. Pete Bain offers his opinion that while a Spacemen 3 reunion isn’t very likely, “the hostility between Jason and Sonic has subsided over the years.” In fact, had Kember and Pierce’s schedules permitted, MAGNET was ready to pose them together for photos to accompany this story.

“It was put to me that we’d be wearing boxing gloves,” says Kember. “But I’d have wanted to do it with the gloves hanging off, about to shake hands!”

“I’ve said that it’s what we’re doing now that’s important; the past is ended,” says Pierce. “But yeah, I’d have done it.”

Thanks and a top o’ the space helmet to: Chris Barrus, Greg Shaw, Long Gone John, Nick Allport, Sid McCain, Bill Bentley and Jeff Honker, alien DJ extraordinaire.