One Last Trip

A (Re)Visit With Spacemen 3’s Jason Pierce and Sonic Boom

by Chris Adams photography: Phil Nichols

HEAVEN.

It’s a funny concept, if you stop to think about it.

It’s always in the sky, somewhere “up there” just outside of attainment, hidden behind the sun, a place you “go to” (if you’ve been “good”) after you burn out your slack bag of bones and shuffle off this mortal coil. It’s hidden in the cosmos, above and beyond the dirt and grime and suffering and struggle that comprises a large part of daily existence on out wretched little rock. Here’s the catch – “everyone wants to go there, but nobody wants to die,” as the saying goes. So whaddafuckdoyado? You try and get as close to it as you can, singe your wings with whatever’s at hand. And “whatever’s at hand” is quite often one of the following: religion, alcohol, frugs, and that slippery little bitch called “love.” These manifestations of the ecstasy/oblivion existential coin-toss are, ironically enough, collectively responsible for more deaths than anything else, except time and possibly starvation. How’s that for a vicious fucking orbit?

And then there’s music. A collection of tones and notes, when properly arranged, can temporarily induce the longed-for transcendent effects, and, as far as I can tell, with no reported deaths. (That said, strand me at a Journey reformation show and some motherfucker’s gonna get it.)

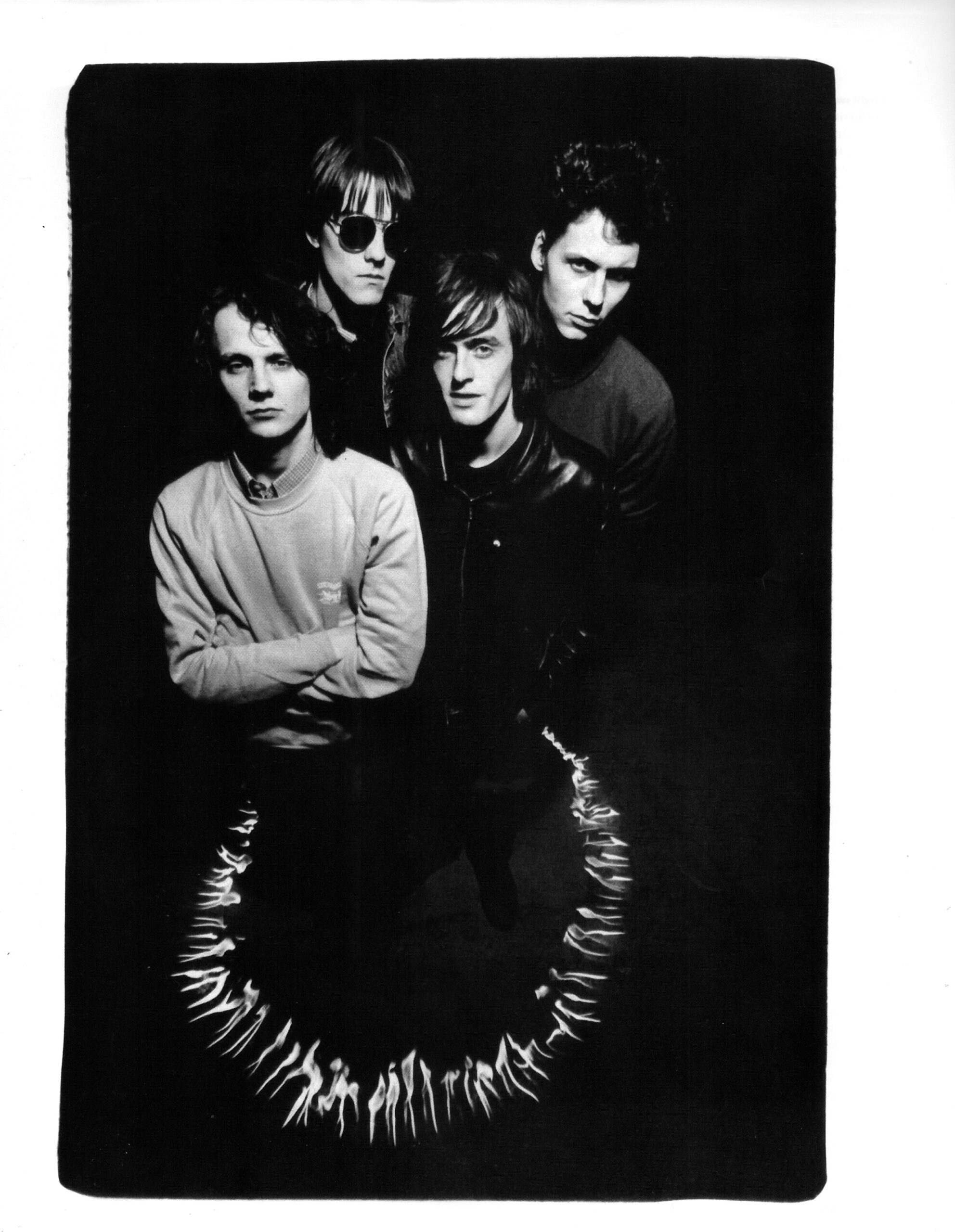

Few if any other rock bands in recent history have so directly explored and documented this search for transcendence than Spacemen 3, both with their avant-garde sonic experiments and their lyrical themes. The band, co-captained by psychonauts Jason “Spaceman” Pierce and Peter “Sonic Boom” Kember, first set their sights sjyward in 1982, and jettisoned their debut Sound of Confusion in 1986. The droning throb and crunch of the album was purposely intended to be an homage to the band’s proto-punk influences, to the point where almost half the songs were covers. (The 13th Floor Elevators’ “Rollercoaster,” the Stooges’ “Little Doll” and “Mary Anne” by Juicy Lucy were all pummelled into slabs of submission.) But the band didn’t really blast off until the release of their sophomore effort, 1987’s Perfect Prescription, which revealed a love of gospel music, slow-mo sunbursts of hallucinatory minimalist psychedelia, and an abject yearning for the unattainable and ineffable. After a few more releases that vacillated between and expanded upon these extremes, the band finally splashed down in 1991 – but not before virtually creating the modern “space-rock” movement and influencing scores of “shoegazer” groups, most notably My Bloody Valentine and Ride. Kember continued with the band Spectrum and largely instrumental satellite side-project Experimental Audio Research (E.A.R.), while Pierce went on to create the more song-oriented symphonies of Spiritualized.

And here they both are now, in separate interviews, Peter and Jason, to discuss their former band’s starship death trip in a rare moment of reflection for two artists who spend their hours mostly gazing forward not backward… and never at their shoes.

Where did you guys spend your formative years?

Peter “Sonic Boom” Kember: It was a little town in England called Rugby, just a small railway town. It’s a nice quiet place, and we never felt we needed to move to a big city to do what we wanted to do.

Jason Pierce: Being from a small town, we had to make our own entertainment, or just join the sort of “mainstream” life, which was pretty grim and small-minded… just raising a family and working in the local business.

How did you first start getting into music? I wouldn’t imagine there was much of a scene around Rigby in the mid- to late-‘70s.

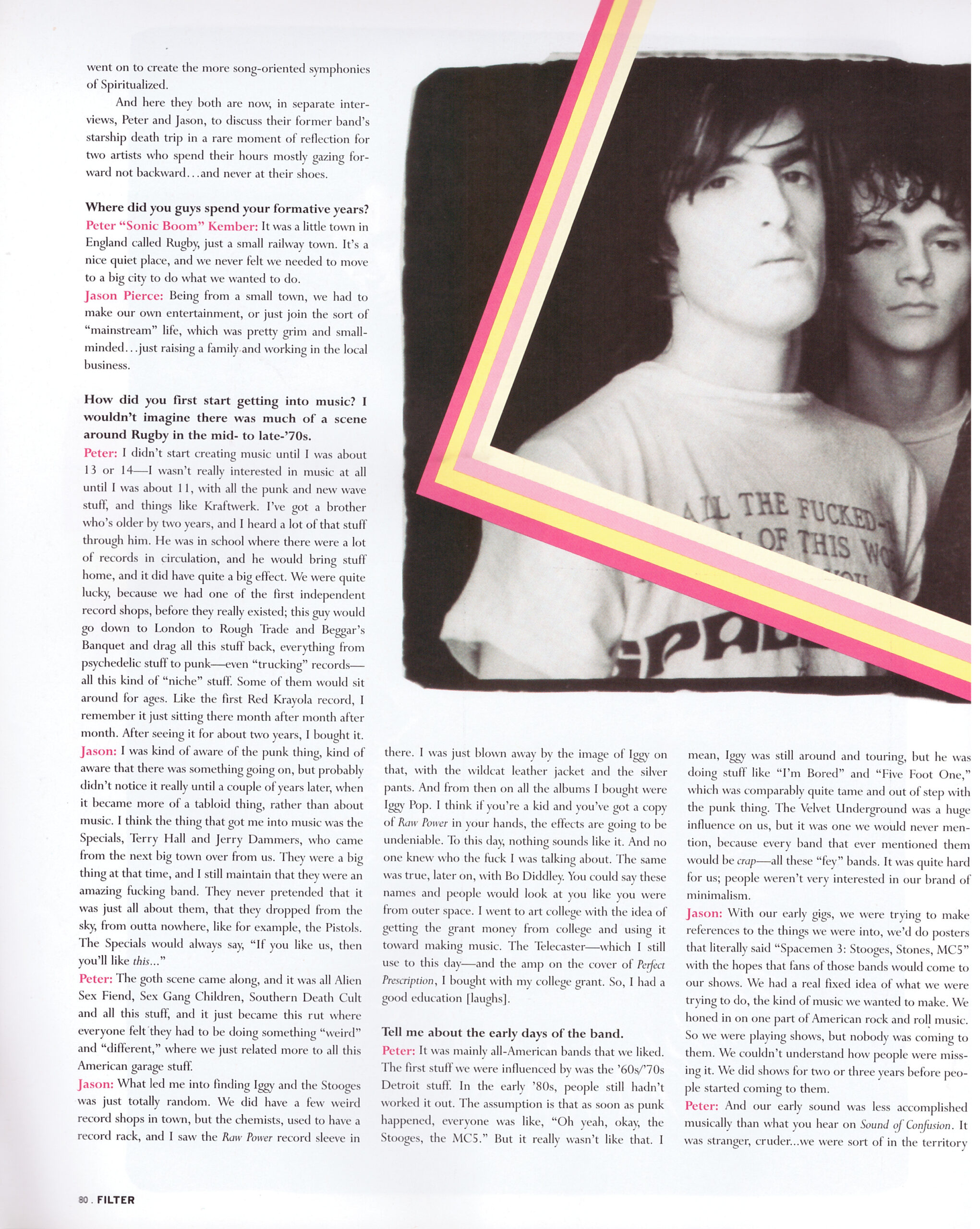

Peter: I didn’t start creating music until I was about 13 or 14 – I wasn’t really interested in music at all until I was about 11, with all the punk and new wave stuff, and things like Kraftwerk. I’ve got a brother who’s older by two years, and I heard a lot of that stuff through him. He was in school where there were a lot of records in circulation, and he would being stuff home, and it did have quite a big effect. We were quite lucky, because we had one of the first independent record shops, before they really existed; this guy would go down to London to Rough Trade and Beggar’s Banquet and drag all this stuff back, everything from psychedelic stuff to punk – even “trucking” records – all this kind of “niche” stuff. Some of them would sit around for ages. Like the first Red Krayola record, I remember is just sitting there month after month after month. After seeing it for about two years, I bought it.

Jason: I was kind of aware of the punk thing, kind of aware that there was something going on, but probably didn’t notice it really until a couple of years later, when it became more of a tabloid thing, rather than about music. I think the thing that got me into music was the Specials, Terry Hall and Jerry Dammers, who came from the next big town over from us. They were a big thing at the time, and I still maintain that they were an amazing fucking band. They never pretended that it was just all about them, that they dropped from the sky, from outa nowhere, like for example, the Pistols. The Specials would always say, “If you like us, then you’ll like this…”

Peter: The goth scene cam along, and it was ll Aliend Sex Fiend, Sex Gang Children, Southern Death Cult and all this stuff, and it just became this rut where everyone felt they had to be doing something “weird” and “different,” where we just related more to all this American garage stuff.

Jason: What led me into finding Iggy and the Stooges was just totally random. We did have a few weird record shops in town, but the chemists, used to have a record rack, and I saw the Raw Power sleeve in there. I was just blown away by the image of Iggy on that, with the wildcat leather jacket and the silver pants. And from there on all the albums I bought were Iggy Pop. I think if you’re a kid and you’ve got a copy of Raw Power in your hands, the effects are going to be undeniable. To this day, nothing sounds like it. And no one knew who the fuck I was talking about. The same was true, later on, with Bo Diddley. You could say these names and people would look at you like you were from outer space. I went to art college with the idea of getting the grant money from college and using it toward making music. The Telecaster – which I still use to this day – and the amp on the cover of Perfect Prescription, I bought with my college grant. So, I had a good education [laughs].

Tell me about the early days of the band.

Peter: It was mainly all-American bands that we liked. The first stuff we were influenced by was the ‘60s/’70s Detroit stuff. In the early ‘80s, people still hadn’t worked it out. The assumption is that as soon as punk happened, everyone was like, “Oh yeah, okay, the Stooges, the MC5.” But it really wasn’t like that. I mean, Iggy was still around and touring, but he was doing stuff like “I’m Bored” and “Five Foot One,” which was comparably quite tame and out of step with the punk thing. The Velvet Underground was a huge influence on us, but it was one we would never mention, because every band that ever mentioned them would be crap – all these “fey” mands. It was quite hard for us; people weren’t very interested in our brand of minimalism.

Jason: With our early gigs, we were trying to make references to the things we were ito, we’d do posters that literally said “Spacemen 3: Stooges, Stones, MC5” with the hopes that fans of those bands would come to our shows. We had a real fixed idea of what we were trying to do, the kind of music we wanted to make. We honed in on one part of American rock and roll music. So we were playing shows, but nobody was coming to them. We couldn’t understand how people were missing it. We did shows for two or three years before people started coming to them.

Peter: And our early sound was less accomplished musically than what you hear on Sound of Confusion. It was stranger, cruder… we were sort of in the territory of the Godz or something like that – not as raw as say the Electric Eels, but we were definitely still finding our sound. You can hear some of that stuff on this album of demos that came out called For All the Fucked Up Children of the World. We were also finding our feet writing. We would write our own music and use other people’s lyrics – like our song “O.D. Catastrophe” had a lot of words that were lifted directly from The Stooges’ “T.V. Eye.”

How did you come up with the name of the band?

Jason: We were really into the Cramps and the Gun Club and that kinda stuff… and for some reason, “The Spacemen” just seemed to sort of fit with their vibe. The 3 came later, Out drummer did a poster that said, “The Spacemen: Are Your Dreams 3 Sizes Too Big?” and from 200 feet away all you could make out was “The Spacemen 3” and that just seemed a good way to go.

I remember reading press about some of your early gigs, and you caused a little bit of an upset by playing shows sitting on chairs with your backs to the audience. Was that an intentional smirk of anti-showbiz irony, or was there more to it?

Jason: It was purely spectacle, purely spectacle [laughs]. No, it was because you could play better. Like, when you’re in the studio, trying to record something, you sit down – it’s easier. So it was that and… well, quite often, not being physically able to stand up for an hour and a half [laughs].

Peter: We did it partly because it looked really cool – and we were never inclined to jump around and all that stuff – and partly because, when you’re playing 20-minute songs, you have to really concentrate. And also, the wah-wahs we used to play, they were a lot easier to play if you could keep the weight of your body so you didn’t have to balance on the other foot. Also, playing the same simple thing again and again can sometimes be harder than to play a song that has lots of changes in it. But it’s weird, I always thought Jason had a lot more presence sitting down than he did standing up. I know that sounds kinda strange. We tried to make up for our lack of movement with these revolving lights we used to buy. We used to bring them home and take acid and try to figure out which ones had the coolest patterns, which ones worked well together. We didn’t really use spots much; it was all strobes. Which is one of the reasons there’s hardly any videos of early Spacemen 3 – you just can’t see anything. We were trying to drag people into our own little world.

That sounds like what the Velvet Underground were sort of trying to do with those Exploding Plastic Inevitable shows at the Dom in 1966, where the heavy strobes and projected films were partially intended to take the visual focus off the band, the “stars of the show” and make it much more of an overall sensory experience for the audience. Those Velvets shows also utilised a lot of heavy repetition, volume, and noise, to see what kind of effects that might have on an audience. “Industrial” artists like Boyd “Non” Rice and Throbbing Gristle also talked about the potentially transformative qualities of those sonic extremes. Was your use of those same elements as experimentally motivated?

Peter: With repetition, you start to hear different things that evolve and change, even though it’s the same thing being repeated. It’s very much the same thing. It sucks you in. We used to call it “hypnotony.” We experimented with that in several ways, with more free0form sounds and different types of repetition, to try and get different effects, to capture different moods. Spacemen 3 was very much about trying to reflect the moods of a very specific type of audience… should they be out there somewhere.

Jason: I think honestly a lot of it had to do with lack of ability, like playing (the Stooges’) “Little Doll” with two chords rather than three and thinking we could get away with it. I’ve always said that I don’t think rock and roll is about talent – and I don’t think we were all that talented. Rock and roll is about putting a guitar around your neck and slamming away at certain notes or chords that produces a level of excitement. It was like, “How much enjoyment can be produced by something this primitive?” It was also that Bryan Gregory (of the Cramps) -type thing, or (Suicide’s) Martin Rev – just finding the right note and sticking with it, rather than trying to expand upon it. Sometimes when you’re very learned in something, you have to unlearn it to do really well. Like an artist, say, Picasso, they almost start to draw like a child again, with like three strokes, and it’s not through lack of knowledge. But to be honest, when we started, we just didn’t have that knowledge, so we didn’t have to unlearn anything.

Generally speaking, the main theme I see running through all the Spacemen 3 records is transcendence. On a pure musical level, both repetition and noise – literally, “the sound of confusion” has been used for eons with the intention a transcendent effect in the listener – I’m referring specifically to Indian ragas and some Haitian Voudon music, where the sonic overload is meant to drive you literally out of your mind. At the other extreme, very quiet, minimal music has been utilised to guide the listener inwards, toward a spiritual self-awareness – and you can find that kind of music in the meditation tapes at your average “crystals and incense” bookstore. You can also hear that pursuit of transcendence in Southern Baptist gospel choirs – and Spacemen 3 referenced gospel music and religious imagery regularly. Why this recurring thread?

Jason: I think that was primarily a result of what we were listening to at the time. You don’t listen to a track like the Velvet Underground’s “Sister Ray” or “Black to Comm” by the MC5 and not be immensely moved by it. That’s the kind of feeling we wanted to put into our music, we wanted to play music that was going to produce some movement within you, it was definitely gonna take you somewhere. The appeal of gospel for me was the whole fervour of if – especially the Staple Singers – it just sounds unlike anything you’ve ever heard before.

Peter: I’ve always been attracted to gospel music. There’s something about the purity of what the people are putting into it, the energy of the feeling they’re trying to encapsulate in songs that are quite often written in a very simple form, but they’re incredibly emotive and incredibly powerful. I mean, I’m sure that the Staple Singers put a lot of energy and effort into their singing – they don’t sound like they’re filing their nails or reading a comic at the same time. They sound like they’re totally into it. We were always trying to capture these very human emotions.

Yeah, but transcending something means you’re trying to remove yourself from wherever you are toward some perceived better condition; it’s a response toward suffering, basically.

Peter: Well, if you’re human, you get scarred, and with Spacemen 3 we’d sort of bear out those scars in music: they would be transposed into the music. I do believe it’s easier to make good music if you are suffering, or at least aware of suffering. I think it’s hard to make good music when people are pandering to you with endless amounts of money or what have you… there’s something more inspiring about being in a car wreck than going shopping. I find it hard to write a song about, say, feeding the cat.

Quite often drugs are used for a transcendent effect, or at least an escapist effect, and there’s certainly no shortage of drug references in the Spacemen 3 catalog. An album title like Taking Drugs to Make Music To Take Drugs To spells that out pretty clearly. I read somewhere that Perfect Prescription was actually created as a conceptual companion piece, or aural guidebook, for dropping acid.

Peter: That has been suggested before, but that wasn’t really the case. Although drugs are a thematic link through that album, it’s not meant to be quite as specific as that. It was our policy to have an ambivalence to that side of stuff, so more people could relate to it. We were trying to be a little unspecific about the lyrics in general, without making them totally wishy-washy. “Walking With Jesus” – I’m sure means more to a lot of people than what it was actually written about.

Jason: I think, at the time, we kind of saw our whole catalog as being a companion piece to taking drugs. That’s just where we were at. The songs we were writing were about our own experience, and experiences of people that we knew. At the time, it seemed the only people writing music that directly referenced drugs were ourselves and the Butthole Surfers. Everyone else seemed content to pretend that it wasn’t part of normal life. And it’s not just in music: drugs are a part of plumbing, part of mechanics, part of any other life you’d care to mention. Even now, people like to say that it’s only on the extremes of life where things like that occur. And that’s just absolutely, categorically not the case.

I think that’s interesting, because it calls what’s considered a “drug” into question. The same people who are so vociferously promoting the “war on drugs” are the same ones keeping you “doped up with religion and sex and TV.” And why are the two martinis after work socially acceptable, and highly-taxed cigarettes legal, but a couple of lines of coke “class D”?

Jason: Absolutely. What’s got me on a life-long trip is tobacco. I smoke over 60 a day.

Your final album, Recurring had an element of portent about it. On previous records, songs were credited to both of you, this album had the distinction of one side of “Sonic Boom” songs, the other side Jason songs. And after that, you broke up. What led to the fallout?

Peter: I think one of the main things was that Jason just stopped writing songs. For a long time the band had been just me and Jason, with different players. Jason and I were the core, and we always worked very closely together. And then he started this relationship, and it seemed like he wanted to put more time and effort into the relationship more than the band, and he stopped writing stuff – at least, he stopped writing stuff with me. Plus, there were egos involved, mine included, and some money issues. No one wanted to do any of the management, administrative side of things, so I ended up doing all that. It became like, “Anything that goes wrong with the band, it’s your fault.” But if anything goes right, then it was, “That’s the way it should be because we’re a great fucking band.” So it was a kind of thankless job. To be fair, Jason did put quite a lot of effort into that side of things early on, but on the whole, I ended up doing that stuff by default. Plus, I was the only one in the band who had a car, so I had to ferry everyone and all the equipment about. It was a fairly traumatic breakup… plus the record label decided it was a good idea to sell Recurring off the back of the fact that the band was arguing, and there was a lot of shit-stirring going on within the press. The English press used to love that crap.

Jason: From where I stood, Pete stated claiming a lot of songwriting credits for himself, and I thought I’d cut him so much slack in the early years… basically, we had an agreement that we’d share the credits. I mean, if you write your own songs, that’s fine, but he started to claim the credits on sings that we definitely co-wrote, things like “Repeater” and “Suicide.” I thought that indicated that there was no future in what we were doing. And by the end, we were playing “Revolution” twice nightly… it just felt like we were done. We were producing music for the audience, when we should have kept producing music for ourselves.

Is there any chance you’d ever work together again?

Peter: I’d like to think so, but I haven’t seen any sign of that from Jason. We haven’t spoken in a long, long time. It was a pretty traumatic split. I’ve tried to communicate with him but hear nothing back. A lot of bad blood went under the bridge, but I’d like us to work together again.

Jason: No, that’s water way under the bridge. From where I stand, I’ve got the greatest band in the world going right now, and I’m not saying that in an adolescent way. And I think I’ve moved so far from what the Spacemen were doing that there’s no point in revisiting it. I don’t want to do any retreads and cover old ground. I want to continue making music that exceeds my own expectations. Plus, I can’t kind of think of any band that’s re-formed that’s any better than what they were, and generally they’re kind of worse than my memory of them. And that’s bad, because rock and roll is built around your memory of it, that kind of mythology is so important, whether it’s Iggy Pop’s exploits, or Robert Johnson selling his soul.