Taking drugs to inspire scenes to take drugs to, two cosmic voyagers lose themselves – and their friendship – in chaos, drone and deep-space drift. By Pete Watts

If shoegaze was, in part, a dialogue between chaos and control, then few bands embodied that more dramatically than Spacemen 3, a group whose love of drone and guitar effects had an inspiring impact on the bands that followed. While their biography would include various members over the years, the band’s creative heart consisted of Jason Pierce and Pete Kember, who for much of Spacemen 3’s career went by the names J Spaceman and Sonic Boom. The friends form a fascinating case study of what can happen when two musicians begin from precisely the same point of origin and then expand outwards to trace completely different musical and creative paths. The pair even shared a birthday, like cosmic twins exploring alternative realities on a single timeline.

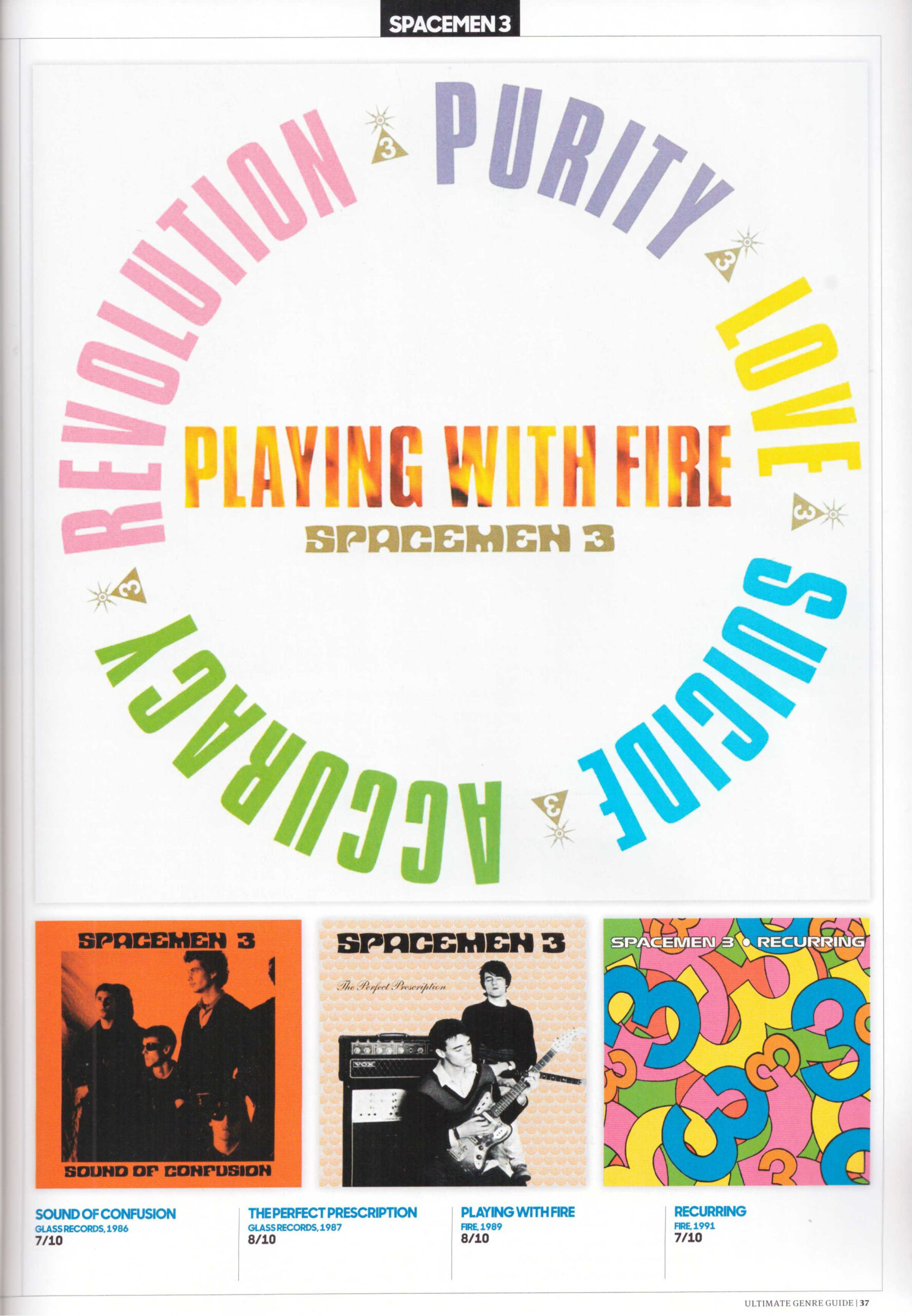

From 1986’s Sound Of Confusion to 1991’s Recurring, the duo took diverging journeys from their original shared love of Suicide, Stooges, distortion and drone. While Kember then delved deeper into chaotic reverb and disorientation, Pierce explored the more uplifting, soothing balm of gospel, as if one was coming at drone from the avenue of Velvet Underground and the other via the Master Musicians Of Joujouka. The sound of Spacemen 3 is the gradual unmooring of Kember and Pierce’s combined interests, which finally became completely untethered on Recurring, an effectively posthumous recording on which the two artists took a side each to expand their individual visions. They even took opposing views to the term “shoegaze”; Kember was sometimes for, Pierce resolutely against.

Appropriately perhaps, Spacemen 3’s standout album, 1989’s Playing With Fire, came pretty much precisely at the point the pair were preparing to separate, in the process forging a record that would inspire some of the most enduring qualities of shoegaze. Guitars shimmer and glaze, beats repeat, vocals are drawled and drowned in fuzz; the music is immersive, textural, dreamlike, suspending the listener in a womb of sound. And then in the middle of that, the band drop something like “Revolution”, a thrilling explosion of overlapping guitars and propulsion that transmits an awful lot of energy and excitement through very few chords, reminding listeners that at heart, this is a rock’n’roll band with a desire to derange.

As a band disposed to reinventing 1960s psychedelia for the less utopic 1980s, Spacemen 3 were operating in similar waters to many bands that would come to be corralled under the nebulous label of shoegaze. Ride and Chapterhouse supported Spacemen 3, while the band shared bills with MBV and musical sensibilities with Loop, who Kember and Pierce accused of imitation. They would be a profound influence on later shoegaze-related artists such as The Brian Jonestown Massacre and The Black Angels, while the 1998 A Tribute To Spacemen 3 album featured contributions from the likes of Mogwai, Low, Arab Strap and Bardo Pond.

Of course, Spacemen 3 never actually gazed at shoes – in fact they often played gigs while sitting on chairs – but they shared a love of atmosphere, effects and pedals, coaxing new and rare sounds from vintage kit. What differentiated Spacemen 3 from their immediate peers – Loop excluded – is the ferocity with which they went about their work. Spacemen 3’s sound evolved and fluctuated, but it was almost always tough. Unlike the whimsy of British ‘60s psychedelia or the Paisley Underground or the more spectral qualities of classic shoegaze, Spacemen 3 were muscular and dirty, birthed in the divisive politics of 1980s Britain. It’s surely no coincidence that Spacemen 3 came from the Midlands, the heartlands of British heavy metal, and some of that heritage seeps into their sound.

Spacemen 3 formed at Rugby Art College in 1982 and, after haphazard early exchanges, were playing regular sessions at the Black Lion in Northampton by 1985, serving up extremely raw and repetitive psychedelia. You can get a taste of their early sound on the magnificently titled Taking Drugs To Make Music To Take Drugs To, a decent recording of early demos that acted as a warm-up for their debut album. Sound Of Confusion came out on Glass Records in 1986. Recorded in Birmingham as a four-piece – Pierce and Kember on guitars, with Pete Bain on bass and Nicholas Brooker on drums – it sounds like a cross between the Stooges and JAMC, featuring a cover of “Little Doll” by The Stooges as well as a track called “OD Catastrophe”, that began life as a one-chord 20-minute drone heavily modelled on “TV Eye”. It is genuinely quite disturbing, with the central guitar parts underwritten by moaning effects that sound like whale song, if the whale was being tortured.

The band’s own songs are pretty good – opener “Losing Touch With My Mind” has a splendid drawl and introduces their psychedelic krautrock style, while “Hey Man” is an early indication of how Pierce’s love of gospel could synch with psych – but the cover of The 13th Floor Elevators’ “Rollercoaster” is a rumbling, riotous highlight. A 17-minute live version featured on the debut single “Walkin’ With Jesus”, that followed shortly after the album.

Second album The Perfect Prescription came out in 1987. By now the band had a new drummer – Brooker refused to wear shoes, so was replaced by Stewart “Rosco” Roswell – and were moving towards a less psychotic sound, including acoustic guitar and moments of studies serenity as well as passages of slamming guitar. The attentive reader may have already noticed that Spacemen 3’s music is riddled with drug references and it’s questionable whether any rock band of their era tried so hard and so unambiguously to replicate the drug experience in their music. The hallucinatory, transportive properties of shoegaze would often get repackaged as “dream pop”, but for Spacemen 3 music was an unapologetically narcotic exercise – or to put it another way: Taking Drugs To Make Music To Take Drugs To. It’s something that Pierce in particular would continue [to] explore throughout his career, most famously through the innovative packaging for Spiritualized’s Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space, which presented the CD as a pill in a foil packet.

On The Perfect Prescription that manifested itself as an explicit attempt to structure the album like the onset, peak and comedown of a trip. Tracks have titles like the gospel-infused “Come Down Easy” and instrumental “Ecstasy Symphony”, making Spacemen 3 one of the first rock bands to reference MDMA – the group encountered the early rave scene at pre-club gigs in Hackney. But there was something much harder at play – as shown by opiate-tinged final track “Call The Doctor” and the previously mentioned “OD Catastrophe”. Shoegaze has the capacity to transport the listener in a disorientating but strangely comforting mesh of overlapping guitars and sonic effects, and Spacemen 3 would use this to make a direct connection to the suspended state of opiate use. No wonder their hometown of Rugby was widely re-christened “Drugby”.

The pair were by now well versed in ‘60s culture – there’s a Red Krayola cover on The Perfect Prescription – and would have known that the drug-taking hedonism of the hippie movement was sometimes seen as a way of providing a shortcut to spiritual nirvana. As a result, many heads later found themselves exploring yoga, meditation, trepanation and other activities that promised sustained religious enlightenment with or without the use of drugs. That sense of spirituality – of seeking an altered state that takes you closer to God – runs replete through Spacemen 3’s music, whether the duo are worshiping at the alter of gospel, heroin or Lou Reed. The lyrics are peppered with religious references, while debut single “Walkin’ With Jesus” draws a straight connection between religion and drugs that was originally even more obvious – the line “So listen sweet lord please forgive me my sins/’Cos I can’t stand this life without all of these things” originally ended “without sweet heroin”.

Spacemen 3 saw out their Glass contract in February 1988 with a heavy live album, Performance, emphasising their garage rock origins. By the time the band returned to the studio to record Playing With Fire they were signed to Fire Records and Pierce and Kember were writing almost completely independently of each other. They were now, finally, living up to their name by operating as a three-piece, with the excellent Will Carruthers joining them on bass. Drums came from a machine. The album was conceived and recorded in somewhat chaotic circumstances but it’s still their masterpiece, from the genius minimalism of Kember’s “How Does It Feel” – composed using his new, effects-heavy Vox Starstream guitar – and his raucous “Revolution” to Pierce’s breathtaking “Come Down Softly To My Soul”, with guitars layered like an Italian dessert, and the epic closing gospel of “Lord Can You Hear Me?”. Here Spacemen 3 were finally stepping away from their influences into unique and uncharted territory.

Despite the excellence of the music and songs that extolled the complex virtues of love, this was not a happy time. Pierce and Kember came to physical blows in the aftermath, literally fighting over credits – Kember wanted sole credit for six songs; Pierce felt three should be classed as co-writes because of his contribution. In the end, only one song is credited as a dual composition, the classic “Suicide”, a one-chord 11-minute drone that shows how much the group had grown musically since the similar “OD Catastrophe”. It’s every bit as relentless but doesn’t make you want to pull out your own teeth by way of light relief.

The pair also disagreed over what should be the lead single. “Revolution” was the obvious choice and was eventually released in November 1988. Ironically for a band that were pretty much ready to call it a day, “Revolution” became an indie hit, giving Spacemen 3 a commercial boost just as they were about to implode. The album’s release had been delayed by the argument over credits, but when it came out in February 1989 it received similar acclaim. So although Kember and Pierce were barely talking – Kember seems to have been particularly put out by Pierce’s relationship with girlfriend Kate Radley – the pair continued to work together, touring in increasingly disharmonious circumstances.

Sensibly, Pierce and Kember were already eyeing parachutes. Kember had recorded an entire solo album around the same time as Playing With Fire, and finally released the downbeat Spectrum in 1990. It contains songs he considered too miserable to record with Spacemen 3, with several worthwhile moments such as the mono-chord “Rock N Roll Is Killing My Life” and the Primal Scream pre-empting “Pretty Baby”. Kember would return to use Spectrum as a musical vehicle several times over the following decades. At this point, he was widely considered to the lead talent in Spacemen 3 and therefore the member most likely to enjoy solo success. However, unbeknownst to Kember, Pierce was jamming with the other three members of Spacemen 3 – in the wake of Playing With Fire, the band had expanded to a five-piece with the addition of Mark Refoy on guitar and drummer Johnny Mattock. This Kember-less four-piece would coalesce into Spiritualized, whose debut single, 1990’s “Any Way That You Want Me”, marked the first time Kember became aware of their existence, completing the parent band’s dissolution.

Before that happened, Spacemen 3 had a final album to release. Recurring was a further departure from the sound established by Playing With Fire, unsurprisingly given that the minimal co-operation that went into that recording had now dwindled to nothing. Kember and Pierce eventually agreed to record and produce their own compositions with their own musicians, delivering a side of music each to confirm the drift that had set in almost from the outset – the CD release separates this concept by plonking a very good collaborative Mudhoney cover, “When Tomorrow Hits”, slap bang in the middle like a garage-rock windbreak.

The first side showcases Kember’s optimistic, ecstasy-enabled drone-pop, a lovebomb of repetition, treated guitars and synths, creating a sound that edges towards Manchester’s baggy scene in places – something that made sense when it was written and recorded in 1989 but less so when the album was finally released in 1991. By then, it was Pierce’s side that seemed to point the way forward as Spiritualized were very much up and running. Side two of Recurring is a dry run for Lazer Guided Melodies and all that would follow – beautiful, fragile orchestral hymns about faith and trust, using space more than drone and lyrics that reflect a predisposition to insularity. The twins were finally split asunder, Spacemen 3 had become non – but their influence would be manifold.