Text

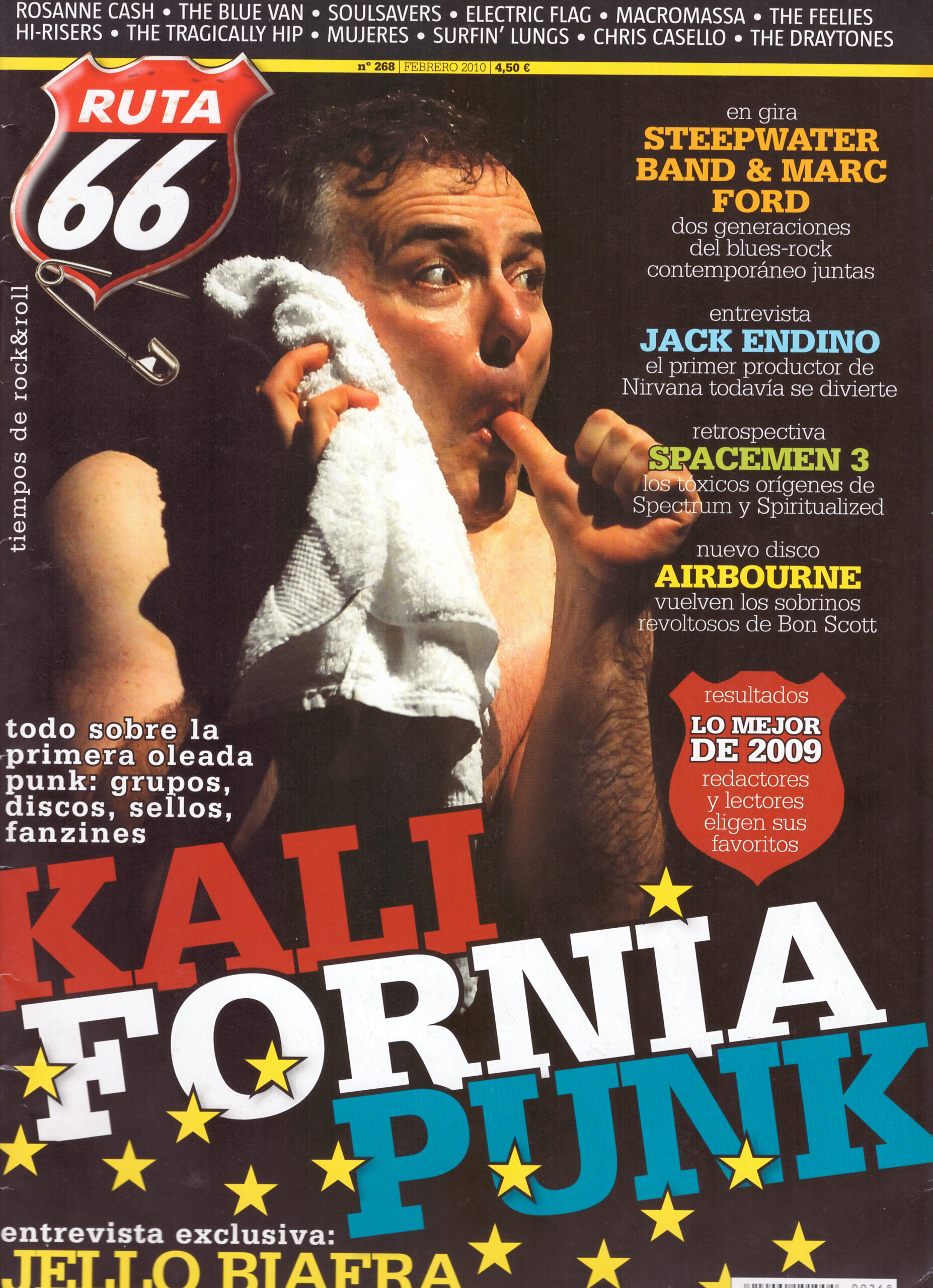

Spacemen 3

HACIA EL INFINITO Y MÁS ALLÁ

Olvidados en el revuelto mar de la actualidad pese a su indudable influencia, estos viajeros astrales se aventuraron por galaxias de iluminación química y resonante minimalismo. Recordamos con Peter Kember/Sonic Boom su delirante historia.

Debemos al rock habernos devuelto el potencial de la música para arrastrarnos al trance. Tras siglos de tradición eurocéntrica, el expansionismo más rítmicos e hipnóticos, resultado del rico influjo afroamericano. Yae n los venturosos años sesenta, la psicodelia rock persiguió el trance con a menudo discutibles resultados, practicando la expansion sensorial a partir de materiales como el blues y el folk, confundiendo la amplitude del paisaje, el vuelo hacia un imaginario espacio exterior, con el trance, cuando a éste se llega desde la obsesiva repetición y la interiorización.

Debemos asimismo a la cultura rock el redescubrimiento de las drogas como sustancias de lúdica expansion mental, tramposa iluminación anímica. Acompañaron a los pioneros del jazz y a los del rock en la forma de anfetamina o heroína, transformándose más rated en marihuana y ácido para ilustrar aquellas utopías jipis prontamente desnortadas. Sería la tercera generación del rock la que se beneficiaría en los setenta, no solo de todo lo cocinado musicalmente hasta la fecha, también de una panoplia estupefaciente que unía antidepresivos con opiáceos en peligroso vademecum.

Pocos grupos amamantados en esa época representan la alianza entre sustancias ilegales y sonido electrificado como los británicos Spacemen 3. Naturales de Rugby, Warwickshire, Reino Unido – Kember prefiere llamarla “Drugby” – su vision de la psicodelia quedaba más próxima a la demencia de 13th Floor Elevators que a la bonhomía de Grateful Dead, su querencia por el trance se fundamentaba en el minimalismo de Bo Diddley y Stooges, su admirative actitud ante los psicotropos anhelaba una ingenua espiritualidad.

Como las mejores historias que nos ha deparado el rock, ésta acabó antes de haber empezado. Spacemen 3 estaban llamados a la implosion por las mismas rezones por los ochenta, al conocerse Peter Kember (alias Peter Gunn primero, definitivamente Sonic Boom), desnaturalizado vástago de una familia acomodada, y Jason Pierce (alias J. Spaceman), de orígenes más modestos, en una escuela de arte. Kember había sido expulsado del instituto por su comportamiento y había desarrollado una adicción a la heroína, sin que sus padres lo sospecharan, lo que acabaría llevándole a una clínica de desintoxicación, de la que saldría hecho afanoso prosélito de toda sustancia alteradora de la consciencia.

Pierce, que había Partido junto a Kember de la raíz común, un sonido entre el núcleo duro del rock psiquedélico y la elevación sensorial a la que conduce el minimalismo armónico, apenas balbuceaba abrumado por la desacomplejada verborrea de Kember, que precisamente por mostrar más llamativamente su empeño y vocación fue tomado por el líder cuando ambos contribuían por el líder cuando ambos contribuían por igual a la subterránea adisea tóxico-musical.

Kember enumeraba las influencias transatlánticas (Velvet Underground, Suicide, Cramps) y mencionaba a coetáneos británicos (Jesus & Mary Chain, Birdhouse, Perfect Disaster, Hypnotics). Lanzaba diatribas contra quienes les comparaban con Hawkwind, contra los nuevos totems underground americanos Sonic Youth o Dinosaur Jr., y especialmente contra su nemesis Loop, formados por un fan de Spacemen 3 que no tuvo reparos en “inspirarse” en su sonido e imagen.

Hoy minimiza la influencia canónica de Velvet y Stooges, reconociendo vía electronica: “No creo que esas bandas sean la Fuente de toda sabiduría. Y si lo son, es ahora cuando realmente Podemos afirmarlo. Pero, en efecto, sentíamos que estaban perforando la veta principal”. Niege asimismo la paradoja de un sonido que abarcaba desde los MC5 más furibundos al Brian Wilson de Smile. “Son periodos distintos de la banda”, puntualiza. “Apenas se daba esa dicotomía. Naturalmente que la mezcla de influencias era inusual, pero también era algo inconscientemente consciente. Como todas las cosas, el sincretismo es lo que es…”.

Por su parte, en las entrevistas, Jason se sumía en la pasividad del fumeta aletargado y asentía con monosílabos. Aquel desequilibrio era obviamente la semilla de futuras disensiones que se agravaron cuando, alrededor del cambio de década, Kember puso en marcha el Proyecto paralelo Spectrum y Pierce reaccionó planeando el despegue de Spiritualized.

Envueltos en neblinas narcóticas y pujantes cacofonías, S3 llegan a una primera formación estable en 1982 y tardarán cuatro años en editar su debut. Son meses de ensayos y ocasionales actuaciones que harán de Pierce y Kember – nacidos el mismo día, 19 de noviembre de 1965! – almas gemelas. “Estábamos tocando en aquella habitación y de pronto algo atravesó el techo, el sonido que escuchábamos parecía venir de otro planeta”, explicaría Pierce sobre la revelación primera de su potencial. “Y eso era S3. Nos encontramos a nosotros mismos hacienda esa música etérea que nos elevaba”.

Inexperto pero explosive, Sound of Confusion (1986) ofrecía delirantes recreaciones de 13th Floor Elevators, los vertiginosos ocho minutos de “Rollercoaster”, y Stooges, “Little Doll”, situados entre dos significativos temas propios que tartan los efectos de las drogas, “Losing Touch with my Mind” al principio, y sus peores consecuencias, la terrible “O.D. Catastrophe” final, donde brillan rescoldos del “Black to Comm” de MC5. Había un componente de aquel garage-rock redescubierto a mediados de los ochenta, pero asimismo una trabajada vena minimalista que les hacía hijos no reconocidos de LaMonte Young y otros gurus drónicos.

“La diferencia entre cómo sonaba nuestra música sobrios o bajo la influencia de varias drogas era absolutamente fundamental para mí”, ha reconocido Kember. “Uno de nuestros máximos intereses era la exploración y alteración de la consciencia y experimentar con el sonido desde estados alterados de la misma. Pero asimismo mantener el lenguaje para retransmitir esos estados a través del sonido y la música. Casi todos los sonidos pueden convertirse en algo que cautiva, asombra, aburre o molesta, mediante una simple extension temporal, su transformación tonal, etc.”.

The Perfect Prescription (1987), considerado el canon S3, rompe en cierto modo aquel impulse de rock subterráneo tras la obertura con la pulsante “Take Me to the Other Side”, inicio de un album planteado como recreación en tiempo real de la experiencia lisérgica. Las beatíficas “Walking with Jesus” y “Ode to Street Hassle” ascienden plácidamente hasta la explosion sensorial de “Ecstasy Symphony/Transparent Radiation”, esta última reinterpretación de un tema de Red Crayola. Instalados en el sosegado bienestar de “Feels So Good”, llega la inminente certidumbre de que ahí empieza el descenso con “Things’ll Never Be the Same” y se teme el angustioso final que expondrá “Call the Doctor”.

Da esta “receta perfects” emana música por cuyos márgenes uno planea atraído por su química constancia y emponzoñada levedad, hasta penetrar translúcidas paredes u acceder a su umbrío interior, sosegado o convulse según el devenir del tema escuchado, la sustancia elegida o el ánimo de quien la ha ingerido. De ese espejismo acostumbra a deducirse un metafórico coponente spiritual que ellos traban mirando de lejos al gospel.

“Se dice que yo y Kember fuimos la esencia de S3, escribíamos las canciones y aportábamos las ideas”, me decía Pierce en 2003 ilustrando esa querencia en principio opuesta a su bagaje rock. “Escuchábamos a Gun Club y a Cramps, y a los 17 años yo ya conocía los discos de los Stooges, sin embatgo, fue Natty Brooker, el batería, quien nos descubrió la múdica de Staple Singers y Mahalia Jackson. Él aportó una serie de cosas que al resto nos habría tomado más tiempo descubrir”.

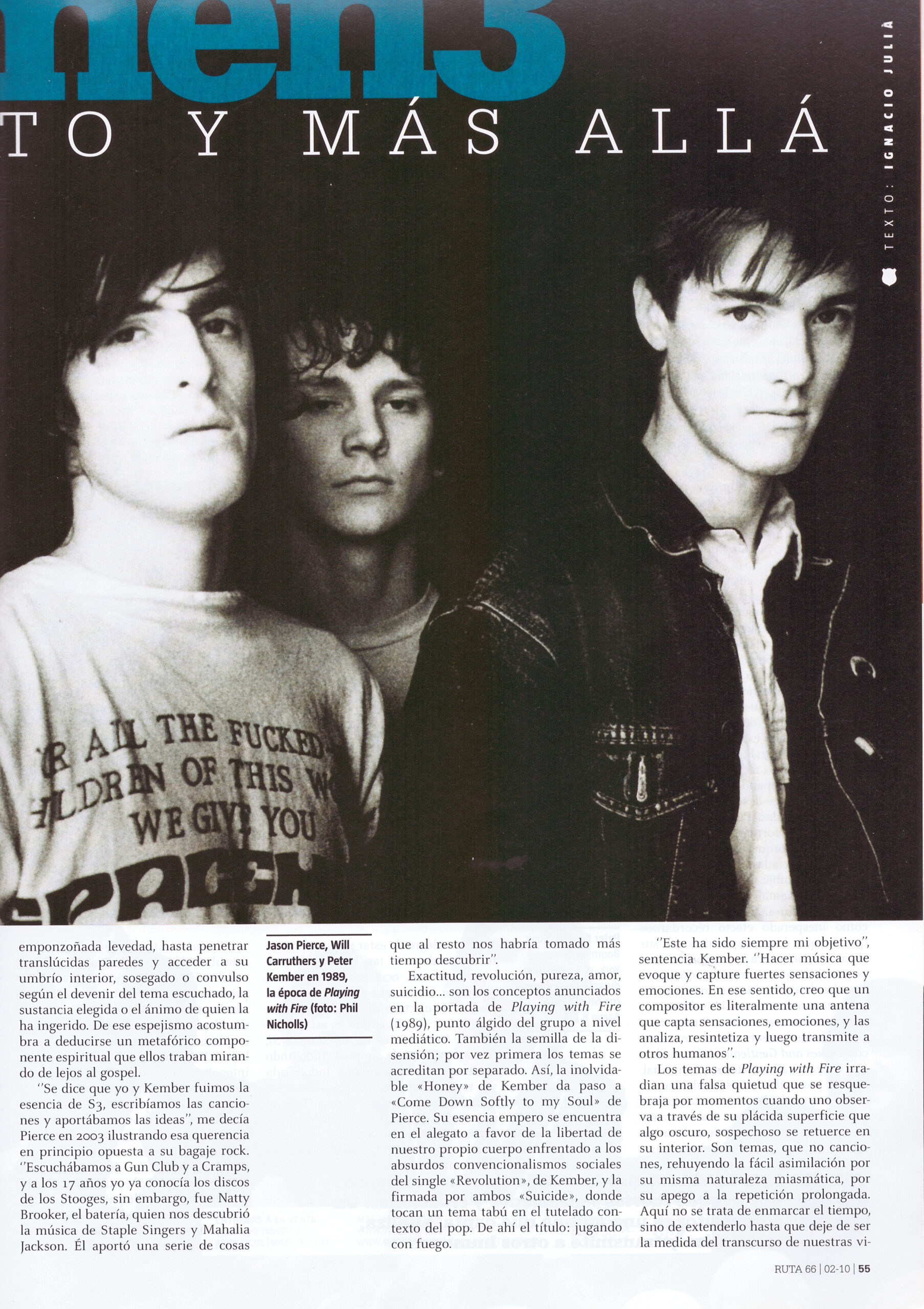

Exactitud, revolución, pureza, amor, suicidio… son los conceptos anunciados en la portada de Playing with Fire (1989), punto álgido del grupo a nivel mediático. También la semilla de la disensión; por vez primera los temas se acreditan por separado. Así, la inolvidable “Honey” de Kember da paso a “Come Down Softly to my Soul” de Pierce. Su esencia empero se encuentra en el alegato a favor de la libertad de nuestro propio cuerpo enfrentado a los absurdos convencionalismos sociales del single “Revolution”, de Kember, y la firmada por ambos “Suicide”, donde tocan un tema tabú en el tutelado context del pop. De ahí el título: jugando con fuego.

“Este ha sido siempre mi objetivo”, sentencia Kember. “Hacer música que Evoque y capture Fuertes sensaciones y emociones. En ese sentido, creo que un compositor es literalmente una antenna que capta sensaciones, emociones, y las analiza, resintetiza y luego transmite a otros humanos”.

Los temas de Playing with Fire irradian una falsa quietud que se resquebraja por momentos cuando uno observa a través de su plácida superficie que algo oscuro, sospechoso se retuerce en su interior. Son temas, que no canciones, rehuyendo la fácil asimilación por su misma naturaleza miasmática, por su apego a la repetición prolongada. Aquí no se trata de enmarcar el tiempo, sino de extenderlo hasta que deje de ser la medida del transcurso de nuestras vidas y se convieta en un todo inexpugnable, se diría infinito. Esto explicaría el fracas commercial del Proyecto mientras las anémicas hordas shoegazer captaban la atención del público.

“Siempre me gusto la música simple, idealmente basada en un zumbido, una nota común sosteniendo la música”, ha dicho Kember. “Lo ideal es un solo acorde, dos acordes están bien, tres valen, cuatro son ya lo convencional. Mi aportación a S3, por encima de mi papel autoral o conceptual, eran básicamente texturas. Simples zumbidos, crescendos lentos pero dinámicos; llevar un acorde desde el proverbial susurro al aullido extremo”.

Recurring (1991) desinflaba en cierto modo el climax alcanzado al disociar la bicefalia, ocupando Kember la primera cara, Pierce la segunda, en grabaciones segregadas. Pierce utiliza a los músicos que formarán Spiritualized para levanter orquestaciones de gospel y blues proyectadas hacia cúpulas catedralicias; Kember adopte una actitud más experimental, aún manteniedo cierta estructure. La disyuntiva tiene como inesperado efecto recordarnos que lo que hacía esplendorosas sus obras anteriores era la tension, la competitividad; que cuando la música se concibe desde las buenas maneras democráticas rara vez resulta valiosa.

Separados sus caminos, Pierce coparía todas las listas fin de año en 1997 con Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space, album etéreo y functional, clásico posmoderno celebrado con la clase de embobada unanimidad crítica que condena a envejecer mal. “Para mí son demasiado pop”, me decía Kember en 2001 sobre Spiritualized. “Y falsamente progresivos en algunos aspectos. Ser progresivo no es malo en sí mismo, aunque el prog-rock tenga tan mala reputación. Los Beatles, por ejemplo, hablaban de su música en términos psiquedélicos, cuando eran progresivos, de hecho mezclaron a Stockhausen con múdica pop en una cancion de tres minutos antes que nadie”.

Sobre la platea semivacía se proyecta un haz sonoro de tensa constancia, electrizante invisibilidad y al parecer ilimitada duración, despojando al espectáculo de vistosidad pero prenándolo de sentido. Con pasmosa concentración, Kember conduce a Spectrum hacia un punto de fuga que solo él parece intuir. Y me reencuentro con una de mis formas musicales favorita, esa obstinada línea recta que te empuja hacia tu interior, avanzando en un solo sentido, voluptuosa pero contenida, una idea que desprecia contenidos para devenir contiente. Es neuvamente la demostración de que un solo acorde, un solo color, una sola palabra, pueden multiplicarse en prolijas fantasias.

Y me allegro de estar vivo, me siento reconfortado ante tan formidable presencia. Se me ocurre una obviedad, or qué funcionará algo tan simple? Recibo vía electronica acorde respuesta de Kember: “Sí, funciona, es así de simple. Sí, funciona, es así de simple. Sí, funciona, es así de simple… Todo, todo el tieompo. Todo el tiempo todo. Cada vez todas las cosas. Cada cosa todas las veces. Todo el tiempo esa cosa. Todo al mismo tiempo… N’est ce pas? Extraer riqueza de muy poca cosa…”.

Por algo se apoda Sonic Boom: su entrega al sonido por encima de cualquier otra consideración le hizo un paria mientras su antiguo socio surcaba los acríticos mares del circuito indie a bordo de los pomposos Spiritualized. Una estimable banda, cierto, pero plegada a los designios de un mercado conformista frente a la libérrima actitud de este loco que se emociona al escuchar el sonido de neumáticos sobre asfalto mojado, que recuerda como epifanías el lejano ronroneo de la lavadora doméstica en los días de la infancia que la gripe le robaba a la escuela, la sinfonia de las cortacespedes poniendo banda sonore a los barrios de las afueras, el glorioso estruendo de los aviones a reacción.

Sin olvidar por ello el factor humanno, como compruebo al mencionar al finado Jim Dickinson, con quien grabó en su studio de Memphis Indian Giver (2008), ultimo album hasta la fecha de Spectrum. “Fue una experiencia memorable hacer aquel disco con mi héroe”, recuerda. O la version de Red Crayola, otra más, en el reciente EP de Spectrum War Sucks (2009).

“Estamos ante uno de los tesoros sin descubrir de la más pura artesanía psicodélica”, postula reivindicativo. “Los primeros discos de Red Crayola predijeron lost también asombrosos primeros dos elepés de Pink Floyd, antes de que empezase su lenta decadencia. También a Kevin Ayres y los intentos bienintencionados pero menos inspirados de Syd Barrett. Mayo Thompson es el genio que nunca perdió el hilo. Cuando nuera todos lo reconocerán”.

Salvando las distancias, lo mismo podría decirse de este creador que ha hecho de la falta de ambición una ventaja artística, de su inclasificable deambular su major patrimonio. Es el precio de esa libertad que algunos pagan gustosos, pues cualquier otra cosa sería impensable.

Flashbacks transparentes

Proliferan las anécdotas sobre las peripecias de este amable politoxicómano inglés. Dean Wareham cuenta que, estando Kember hospedado en su apartamento neoyorquino, le dejaron solo una noche y al regresar el televisor había sido trepanado y destruido sin que el principal sospechoso recordase nada de lo sucedido.

Yo mismo a punto estuve de sufrir una pálida al compartir fumada en el Tanned Tin de 2001. Pero la edad todo lo cura y el demacrado, larguirucho personaje que aquella noche desató una tormenta perfecta desde sus máquinas bajo la marca Experimental Audio Research, se casó hace unas semanas con Sam, emprendedora compañera que parece haber dosificado sus querencias químicas y puesto orden a su Carrera professional.

Acaba de producer un disco, Congratulations, a los norteamericanos MGMT, banda emergente nominada a un Grammy. “Me gusta su honestidad, su humildad”, explica. “Me agrada cómo están llevando esa locura de la fama que se les ha venido encima. Respeto su integridad y, por supuesto, me gusta su música”.

Dado que disfruta de manager confirmado por el registro civil y luce rejuvenecido al haber recobrado sus carnes, sería possible la reunion de S3 ahora que se ha puesto las pilas y Pierce ha visto devaluarse los activos de Spiritualized? Cosas más imposibles se han visto. “Estuve de gira con Yo La Tengo hace años”, suelta Kember. “Si pude aguantar a Ira Kaplan durante una semana, puedo con todo”.

Translation

Spacemen 3

TOWARDS INFINITY AND BEYOND

Forgotten in the troubled sea of today despite their undoubted influence, these astral travelers ventured into galaxies of chemical illumination and resonant minimalism. We remember with Peter Kember / Sonic Boom his delusional story.

We owe it to rock to have restored the potential of music to drag us into a trance. After centuries of Eurocentric tradition, the most rhythmic and hypnotic expansionism, the result of the rich African-American influence. Back in the blissful sixties, psychedelic rock pursued trance with often questionable results, practicing sensory expansion from materials such as blues and folk, confusing the amplitude of the landscape, the flight into an imaginary outer space, with the trance, when it is reached from obsessive repetition and internalization.

We also owe to rock culture the rediscovery of drugs as substances of playful mental expansion, tricky soul lighting. They accompanied the pioneers of jazz and those of rock in the form of amphetamine or heroin, transforming themselves more rated into marijuana and acid to illustrate those hippie utopias that were soon disconcerted. It would be the third generation of rock that would benefit in the seventies, not only from everything musically cooked to date, but also from a narcotic panoply that united antidepressants with opiates in a dangerous vademecum.

Few breastfed groups at that time represent the alliance between illegal substances and electrified sound like the British Spacemen 3. Natives of Rugby, Warwickshire, UK – Kember prefers to call it “Drugby” – their vision of psychedelic was closer to the dementia of 13th Floor Elevators than the Grateful Dead bonhomie, his love of trance was based on the minimalism of Bo Diddley and Stooges, his admiring attitude towards psychotropics yearned for a naive spirituality.

Like the best stories rock has given us, this one ended before it started. Spacemen 3 were called to implode for the same reasons in the eighties, when they met Peter Kember (aka Peter Gunn first, definitely Sonic Boom), a denatured scion of a wealthy family, and Jason Pierce (aka J. Spaceman), of older origins. modest, in an art school. Kember had been expelled from the institute for his behavior and had developed an addiction to heroin, without his parents suspecting it, which would end up taking him to a detox clinic, from which he would be an eager proselyte of every substance that alters consciousness.

Pierce, who had Parted with Kember from the common root, a sound between the hard core of psychedelic rock and the sensory elevation to which harmonic minimalism leads, barely babbled, overwhelmed by Kember’s uncomplexed verbiage, which precisely for showing more strikingly his commitment and vocation was taken by the leader when both contributed for the leader when both contributed equally to the underground toxic-musical adisea.

Kember listed transatlantic influences (Velvet Underground, Suicide, Cramps) and mentioned British contemporaries (Jesus & Mary Chain, Birdhouse, Perfect Disaster, Hypnotics). He launched into tirades against those who compared them to Hawkwind, against the new American underground totems Sonic Youth or Dinosaur Jr., and especially against his nemesis Loop, formed by a Spacemen 3 fan who had no qualms about “getting inspired” by their sound and image.

Today he minimizes the canonical influence of Velvet and Stooges, acknowledging electronically: “I don’t think these bands are the Source of all wisdom. And if they are, this is when we can really affirm it. But, in effect, we felt like they were drilling the main vein. ” He also denies the paradox of a sound that ranged from the most furious MC5s to Smile’s Brian Wilson. “They are different periods of the band,” he points out. “There was hardly that dichotomy. Of course the mix of influences was unusual, but it was also unconsciously conscious. Like all things, syncretism is what it is… ”.

For his part, in the interviews, Jason sank into the passivity of the lethargic stoner and nodded in monosyllables. That imbalance was obviously the seed of future dissensions that were exacerbated when, around the turn of the decade, Kember launched the Spectrum Side Project and Pierce reacted by planning Spiritualized’s takeoff.

Wrapped in narcotic mists and powerful cacophonies, S3 arrived at a first stable line-up in 1982 and it would take four years to release their debut. It’s months of rehearsals and occasional performances that will make Pierce and Kember – born the same day, November 19, 1965! – soulmates. “We were playing in that room and suddenly something went through the ceiling, the sound we were hearing seemed to come from another planet,” Pierce explained about the first revelation of his potential. And that was S3. We found ourselves making that ethereal music that lifted us up ”.

Inexperienced but explosive, Sound of Confusion (1986) featured delirious recreations of 13th Floor Elevators, the dizzying eight minutes of “Rollercoaster,” and Stooges, “Little Doll,” set between two significant themes of their own tartning the effects of drugs, “ Losing Touch with my Mind ”at the beginning, and its worst consequences, the terrible“ OD Catastrophe ”final, where embers of MC5’s“ Black to Comm ”shine. There was a component of that garage-rock rediscovered in the mid-eighties, but also a worked minimalist streak that made them unrecognized children of LaMonte Young and other dronic gurus.

“The difference between how our music sounded sober or under the influence of various drugs was absolutely critical to me,” Kember acknowledged. “One of our main interests was the exploration and alteration of consciousness and experimenting with sound from altered states of it. But also maintain the language to retransmit those states through sound and music. Almost all sounds can become something that captivates, amazes, bores or annoys, by means of a simple temporal extension, their tonal transformation, etc. ”.

The Perfect Prescription (1987), considered the S3 canon, breaks in a way that underground rock impulse after the overture with the pulsating “Take Me to the Other Side”, the beginning of an album designed as a real-time recreation of the lysergic experience . The beatific “Walking with Jesus” and “Ode to Street Hassle” rise placidly to the sensory explosion of “Ecstasy Symphony / Transparent Radiation,” the latest reinterpretation of a Red Crayola track. Installed in the calm well-being of “Feels So Good”, the imminent certainty arrives that there begins the descent with “Things’ll Never Be the Same” and the anguished ending that “Call the Doctor” will expose is feared.

Give this “perfects recipe” music emanates from whose margins one glides attracted by its constant chemistry and poisoned lightness, until penetrating translucent walls or accessing its shady interior, calm or convulsed according to the evolution of the theme heard, the chosen substance or the mood of who has ingested it. From this mirage it is customary to deduce a metaphorical spiritual component that they work by looking at the gospel from afar.

“It is said that I and Kember were the essence of S3, we wrote the songs and contributed the ideas,” Pierce told me in 2003 illustrating that love in principle opposed to his rock background. “We listened to Gun Club and Cramps, and at 17 I already knew the Stooges’ records, however, it was Natty Brooker, the drummer, who discovered the Staple Singers and Mahalia Jackson music for us. He contributed a series of things that the rest of us would have taken longer to discover ”.

Accuracy, revolution, purity, love, suicide… are the concepts announced on the cover of Playing with Fire (1989), the group’s high point at the media level. Also the seed of dissension; for the first time the themes are credited separately. Thus, Kember’s unforgettable “Honey” gives way to Pierce’s “Come Down Softly to my Soul”. Its essence, however, is found in the plea in favor of the freedom of our own body faced with the absurd social conventions of the single “Revolution”, by Kember, and the one signed by both “Suicide”, where they play a taboo subject in the protected context of pop. Hence the title: playing with fire.

“This has always been my goal,” Kember says. “Make music that evokes and captures strong sensations and emotions. In that sense, I think that a composer is literally an antenna that captures sensations, emotions, and analyzes them, resynthesizes them and then transmits them to other humans ”.

The themes of Playing with Fire radiate a false stillness that cracks at times when one observes through its placid surface that something dark, suspicious twists inside. They are themes, not songs, avoiding easy assimilation due to their miasmatic nature, due to their attachment to prolonged repetition. Here it is not a question of framing time, but of extending it until it ceases to be the measure of the course of our lives and becomes an impregnable whole, one would say infinite. This would explain the commercial failure of the Project as the anemic shoegazer hordes captured the public’s attention.

“I’ve always liked simple music, ideally based on a hum, a common note holding the music,” Kember said. “The ideal is a single chord, two chords are good, three are valid, four are conventional. My contribution to S3, above my authorial or conceptual role, was basically textures. Simple hums, slow but dynamic crescendos; take a chord from the proverbial whisper to the extreme howl ”.

Recurring (1991) somewhat deflated the climax achieved by dissociating bicephaly, with Kember occupying the first face, Pierce the second, in segregated recordings. Pierce uses the musicians who will form Spiritualized to lift gospel and blues orchestrations projected onto cathedral domes; Kember adopted a more experimental attitude, still maintaining a certain structure. The dilemma has the unexpected effect of reminding us that what made his previous works splendor was tension, competitiveness; that when music is conceived in good democratic manners it is rarely valuable.

Their paths separated, Pierce would top all the year-end charts in 1997 with Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space, an ethereal and functional album, a postmodern classic celebrated with the kind of gawking critical unanimity that condemns aging poorly. “For me they are too pop,” Kember told me in 2001 about Spiritualized. “And falsely progressive in some ways. Being progressive is not bad in itself, even though prog-rock gets such a bad rap. The Beatles, for example, spoke of their music in psychedelic terms, when they were progressive, in fact they mixed Stockhausen with medical pop in a three-minute song before anyone else.

A sound beam of tense constancy, electrifying invisibility and seemingly unlimited duration is projected onto the semi-empty stalls, stripping the show of eye-catching but making it meaningful. With astonishing concentration, Kember leads Spectrum toward a vanishing point that only he seems to sense. And I am reunited with one of my favorite musical forms, that stubborn straight line that pushes you inward, moving in one direction, voluptuous but contained, an idea that disregards content to become content. It is a new demonstration that a single chord, a single color, a single word, can be multiplied in neat fantasies.

And I am glad to be alive, I feel comforted by such a formidable presence. I can think of a truism, or what will something so simple work? I received an electronic response from Kember: “Yes, it works, it’s that simple. Yes, it works, it’s that simple. Yes, it works, it’s that simple … Everything, all the time. All the time everything. Every time all things. Every thing every time. All the time that thing. All at the same time… N’est ce pas? Extract wealth from very little … ”.

He is nicknamed Sonic Boom for a reason: his dedication to sound above all other considerations made him an outcast as his former partner sailed the uncritical seas of the indie circuit aboard the pompous Spiritualized. An estimable band, true, but folded to the designs of a conformist market in the face of the very free attitude of this madman who is moved to hear the sound of tires on wet asphalt, which recalls as epiphanies the distant purr of the domestic washing machine in the days from the childhood that the flu stole from the school, the symphony of lawnmowers putting a soundtrack to the suburbs, the glorious roar of jet planes.

Without forgetting the human factor, as I can see when I mention the late Jim Dickinson, with whom he recorded in his studio in Memphis Indian Giver (2008), the last album to date on Spectrum. “It was a memorable experience making that record with my hero,” he recalls. Or Red Crayola’s version, another one, on the recent Spectrum War Sucks EP (2009).

“We are facing one of the undiscovered treasures of the purest psychedelic craftsmanship,” he postulates vindication. “Red Crayola’s early records predicted the astonishing first two Pink Floyd LPs as well, before it began its slow decline. Also to Kevin Ayres and the well-meaning but less inspired attempts of Syd Barrett. Mayo Thompson is the genius who never lost the thread. When daughter-in-law everyone will recognize him ”.

Saving the distances, the same could be said of this creator who has made his lack of ambition an artistic advantage, of his unclassifiable wandering his best heritage. It is the price of that freedom that some willingly pay, since anything else would be unthinkable.

Transparent flashbacks

Anecdotes about the adventures of this friendly English multi-drug addict proliferate. Dean Wareham says that, while Kember was staying in his New York apartment, they left him alone for one night and when he returned the television had been trepanned and destroyed without the main suspect remembering anything of what happened.

I myself was about to suffer a pale when sharing a smoke in the Tanned Tin of 2001. But age heals everything and the emaciated, lanky character who that night unleashed a perfect storm from his machines under the brand Experimental Audio Research, got married A few weeks ago with Sam, a fellow entrepreneur who seems to have dosed her chemical wants and put her professional career in order.

He has just produced an album, Congratulations, to the North American MGMT, an emerging band nominated for a Grammy. “I like his honesty, his humility,” he explains. “I like how they are carrying that madness of fame that has come down on them. I respect her integrity and, of course, I like her music. “

Given that he enjoys a manager confirmed by the civil registry and looks rejuvenated after having regained his flesh, would the S3 reunion be possible now that he has put the batteries and Pierce has seen the assets of Spiritualized devalue? More impossible things have been seen. “I was on tour with Yo La Tengo years ago,” Kember says. “If I can put up with Ira Kaplan for a week, I can handle anything.”